I

It was a dark autumn

night. The old banker was pacing from corner to corner of his study,

recalling to his mind the party he gave in the autumn fifteen years

before. There were many clever people at the party and much interesting

conversation. They talked among other things of capital punishment. The

guests, among them not a few scholars and journalists, for the most part

disapproved of capital punishment. They found it obsolete as a means of

punishment, unfitted to a Christian State and immoral. Some of them

thought that capital punishment should be replaced universally by life

imprisonment.

“I don’t agree with

you,” said the host. “I myself have experienced neither capital

punishment nor life-imprisonment, but if one may judge a priori, then in

my opinion capital punishment is more moral and more humane than

imprisonment. Execution kills instantly, life-imprisonment kills by

degrees. Who is the more humane executioner, one who kills you in a few

seconds or one who draws the life out of you incessantly, for years?”

“They’re both

equally immoral,” remarked one of the guests, “because their purpose is

the same, to take away life. The State is not God. It has no right to

take away that which it cannot give back, if it should so desire.”

Among the company was a lawyer, a young man of about twenty-five. On being asked his opinion, he said:

“Capital punishment

and life-imprisonment are equally immoral; but if I were offered the

choice between them, I would certainly choose the second. It’s better to

live somehow than not to live at all.”

There ensued a

lively discussion. The banker who was then younger and more nervous

suddenly lost his temper, banged his fist on the table, and turning to

the young lawyer, cried out:

“It’s a lie. I bet you two millions you wouldn’t stick in a cell even for five years.”

“If you mean it seriously,” replied the lawyer, “then I bet I’ll stay not five but fifteen.”

“Fifteen! Done!” cried the banker. “Gentlemen, I stake two millions.”

“Agreed. You stake two millions, I my freedom,” said the lawyer.

So this wild,

ridiculous bet came to pass. The banker, who at that time had too many

millions to count, spoiled and capricious, was beside himself with

rapture. During supper he said to the lawyer jokingly:

“Come to your

senses, young roan, before it’s too late. Two millions are nothing to

me, but you stand to lose three or four of the best years of your life. I

say three or four, because you’ll never stick it out any longer. Don’t

forget either, you unhappy man, that voluntary is much heavier than

enforced imprisonment. The idea that you have the right to free yourself

at any moment will poison the whole of your life in the cell. I pity

you.”

And now the banker, pacing from corner to corner, recalled all this and asked himself:

“Why did I make this

bet? What’s the good? The lawyer loses fifteen years of his life and I

throw away two millions. Will it convince people that capital punishment

is worse or better than imprisonment for life? No, no! all stuff and

rubbish. On my part, it was the caprice of a well-fed man; on the

lawyer’s pure greed of gold.”

He recollected

further what happened after the evening party. It was decided that the

lawyer must undergo his imprisonment under the strictest observation, in

a garden wing of the banker’s house. It was agreed that during the

period he would be deprived of the right to cross the threshold, to see

living people, to hear human voices, and to receive letters and

newspapers. He was permitted to have a musical instrument, to read

books, to write letters, to drink wine and smoke tobacco. By the

agreement he could communicate, but only in silence, with the outside

world through a little window specially constructed for this purpose.

Everything necessary, books, music, wine, he could receive in any

quantity by sending a note through the window. The agreement provided

for all the minutest details, which made the confinement strictly

solitary, and it obliged the lawyer to remain exactly fifteen years from

twelve o’clock of November 14th, 1870, to twelve o’clock of November

14th, 1885. The least attempt on his part to violate the conditions, to

escape if only for two minutes before the time freed the banker from the

obligation to pay him the two millions.

During the first

year of imprisonment, the lawyer, as far as it was possible to judge

from his short notes, suffered terribly from loneliness and boredom.

From his wing day and night came the sound of the piano. He rejected

wine and tobacco. “Wine,” he wrote, “excites desires, and desires are

the chief foes of a prisoner; besides, nothing is more boring than to

drink good wine alone,” and tobacco spoils the air in his room. During

the first year the lawyer was sent books of a light character; novels

with a complicated love interest, stories of crime and fantasy,

comedies, and so on.

In the second year

the piano was heard no longer and the lawyer asked only for classics. In

the fifth year, music was heard again, and the prisoner asked for wine.

Those who watched him said that during the whole of that year he was

only eating, drinking, and lying on his bed. He yawned often and talked

angrily to himself. Books he did not read. Sometimes at nights he would

sit down to write. He would write for a long time and tear it all up in

the morning. More than once he was heard to weep.

In the second half

of the sixth year, the prisoner began zealously to study languages,

philosophy, and history. He fell on these subjects so hungrily that the

banker hardly had time to get books enough for him. In the space of four

years about six hundred volumes were bought at his request. It was

while that passion lasted that the banker received the following letter

from the prisoner: “My dear gaoler, I am writing these lines in six

languages. Show them to experts. Let them read them. If they do not find

one single mistake, I beg you to give orders to have a gun fired off in

the garden. By the noise I shall know that my efforts have not been in

vain. The geniuses of all ages and countries speak in different

languages; but in them all burns the same flame. Oh, if you knew my

heavenly happiness now that I can understand them!” The prisoner’s

desire was fulfilled. Two shots were fired in the garden by the banker’s

order.

Later on, after the

tenth year, the lawyer sat immovable before his table and read only the

New Testament. The banker found it strange that a man who in four years

had mastered six hundred erudite volumes, should have spent nearly a

year in reading one book, easy to understand and by no means thick. The

New Testament was then replaced by the history of religions and

theology.

During the last two

years of his confinement the prisoner read an extraordinary amount,

quite haphazard. Now he would apply himself to the natural sciences,

then he would read Byron or Shakespeare. Notes used to come from him in

which he asked to be sent at the same time a book on chemistry, a

text-book of medicine, a novel, and some treatise on philosophy or

theology. He read as though he were swimming in the sea among broken

pieces of wreckage, and in his desire to save his life was eagerly

grasping one piece after another.

II

The banker recalled all this, and thought:

“To-morrow at twelve

o’clock he receives his freedom. Under the agreement, I shall have to

pay him two millions. If I pay, it’s all over with me. I am ruined for

ever ...”

Fifteen years before

he had too many millions to count, but now he was afraid to ask himself

which he had more of, money or debts. Gambling on the Stock-Exchange,

risky speculation, and the recklessness of which he could not rid

himself even in old age, had gradually brought his business to decay;

and the fearless, self-confident, proud man of business had become an

ordinary banker, trembling at every rise and fall in the market.

“That cursed bet,”

murmured the old man clutching his head in despair... “Why didn’t the

man die? He’s only forty years old. He will take away my last farthing,

marry, enjoy life, gamble on the Exchange, and I will look on like an

envious beggar and hear the same words from him every day: ‘I’m obliged

to you for the happiness of my life. Let me help you.’ No, it’s too

much! The only escape from bankruptcy and disgrace—is that the man

should die.”

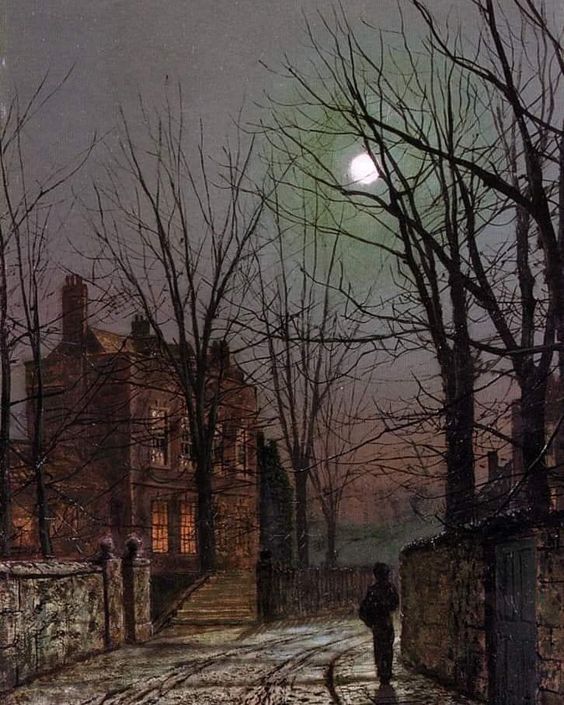

The clock had just

struck three. The banker was listening. In the house every one was

asleep, and one could hear only the frozen trees whining outside the

windows. Trying to make no sound, he took out of his safe the key of the

door which had not been opened for fifteen years, put on his overcoat,

and went out of the house. The garden was dark and cold. It was raining.

A damp, penetrating wind howled in the garden and gave the trees no

rest. Though he strained his eyes, the banker could see neither the

ground, nor the white statues, nor the garden wing, nor the trees.

Approaching the garden wing, he called the watchman twice. There was no

answer. Evidently the watchman had taken shelter from the bad weather

and was now asleep somewhere in the kitchen or the greenhouse.

“If I have the courage to fulfil my intention,” thought the old man, “the suspicion will fall on the watchman first of all.”

In the darkness he

groped for the steps and the door and entered the hall of the

garden-wing, then poked his way into a narrow passage and struck a

match. Not a soul was there. Some one’s bed, with no bedclothes on it,

stood there, and an iron stove loomed dark in the corner. The seals on

the door that led into the prisoner’s room were unbroken.

When the match went out, the old man, trembling from agitation, peeped into the little window.

In the prisoner’s

room a candle was burning dimly. The prisoner himself sat by the table.

Only his back, the hair on his head and his hands were visible. Open

books were strewn about on the table, the two chairs, and on the carpet

near the table.

Five minutes passed

and the prisoner never once stirred. Fifteen years’ confinement had

taught him to sit motionless. The banker tapped on the window with his

finger, but the prisoner made no movement in reply. Then the banker

cautiously tore the seals from the door and put the key into the lock.

The rusty lock gave a hoarse groan and the door creaked. The banker

expected instantly to hear a cry of surprise and the sound of steps.

Three minutes passed and it was as quiet inside as it had been before.

He made up his mind to enter.

Before the table sat

a man, unlike an ordinary human being. It was a skeleton, with

tight-drawn skin, with long curly hair like a woman’s, and a shaggy

beard. The colour of his face was yellow, of an earthy shade; the cheeks

were sunken, the back long and narrow, and the hand upon which he

leaned his hairy head was so lean and skinny that it was painful to look

upon. His hair was already silvering with grey, and no one who glanced

at the senile emaciation of the face would have believed that he was

only forty years old. On the table, before his bended head, lay a sheet

of paper on which something was written in a tiny hand.

“Poor devil,”

thought the banker, “he’s asleep and probably seeing millions in his

dreams. I have only to take and throw this half-dead thing on the bed,

smother him a moment with the pillow, and the most careful examination

will find no trace of unnatural death. But, first, let us read what he

has written here.”

The banker took the sheet from the table and read:

“To-morrow at twelve

o’clock midnight, I shall obtain my freedom and the right to mix with

people. But before I leave this room and see the sun I think it

necessary to say a few words to you. On my own clear conscience and

before God who sees me I declare to you that I despise freedom, life,

health, and all that your books call the blessings of the world.

“For fifteen years I

have diligently studied earthly life. True, I saw neither the earth nor

the people, but in your books I drank fragrant wine, sang songs, hunted

deer and wild boar in the forests, loved women... And beautiful women,

like clouds ethereal, created by the magic of your poets’ genius,

visited me by night and whispered to me wonderful tales, which made my

head drunken. In your books I climbed the summits of Elbruz and Mont

Blanc and saw from there how the sun rose in the morning, and in the

evening suffused the sky, the ocean and the mountain ridges with a

purple gold. I saw from there how above me lightnings glimmered cleaving

the clouds; I saw green forests, fields, rivers, lakes, cities; I heard

syrens singing, and the playing of the pipes of Pan; I touched the

wings of beautiful devils who came flying to me to speak of God... In

your books I cast myself into bottomless abysses, worked miracles,

burned cities to the ground, preached new religions, conquered whole

countries..

“Your books gave me

wisdom. All that unwearying human thought created in the centuries is

compressed to a little lump in my skull. I know that I am cleverer than

you all.

“And I despise your

books, despise all worldly blessings and wisdom. Everything is void,

frail, visionary and delusive as a mirage. Though you be proud and wise

and beautiful, yet will death wipe you from the face of the earth like

the mice underground; and your posterity, your history, and the

immortality of your men of genius will be as frozen slag, burnt down

together with the terrestrial globe.

“You are mad, and

gone the wrong way. You take falsehood for truth and ugliness for

beauty. You would marvel if suddenly apple and orange trees should bear

frogs and lizards instead of fruit, and if roses should begin to breathe

the odour of a sweating horse. So do I marvel at you, who have bartered

heaven for earth. I do not want to understand you.

“That I may show you

in deed my contempt for that by which you live, I waive the two

millions of which I once dreamed as of paradise, and which I now

despise. That I may deprive myself of my right to them, I shall come out

from here five minutes before the stipulated term, and thus shall

violate the agreement.”

When he had read,

the banker put the sheet on the table, kissed the head of the strange

man, and began to weep. He went out of the wing. Never at any other

time, not even after his terrible losses on the Exchange, had he felt

such contempt for himself as now. Coming home, he lay down on his bed,

but agitation and tears kept him a long time from sleeping...

The next morning the

poor watchman came running to him and told him that they had seen the

man who lived in the wing climb through the window into the garden. He

had gone to the gate and disappeared. The banker instantly went with his

servants to the wing and established the escape of his prisoner. To

avoid unnecessary rumours he took the paper with the renunciation from

the table and, on his return, locked it in his safe.