In the town of Vladimir lived a young merchant named Ivan Dmitrich Aksionov. He had two shops and a house of his own.

Aksionov was a

handsome, fair-haired, curly-headed fellow, full of fun, and very fond

of singing. When quite a young man he had been given to drink, and was

riotous when he had had too much; but after he married he gave up

drinking, except now and then.

One summer Aksionov

was going to the Nizhny Fair, and as he bade good-bye to his family, his

wife said to him, “Ivan Dmitrich, do not start to-day; I have had a bad

dream about you.”

Aksionov laughed, and said, “You are afraid that when I get to the fair I shall go on a spree.”

His wife replied: “I

do not know what I am afraid of; all I know is that I had a bad dream. I

dreamt you returned from the town, and when you took off your cap I saw

that your hair was quite grey.”

Aksionov laughed.

“That’s a lucky sign,” said he. “See if I don’t sell out all my goods,

and bring you some presents from the fair.”

So he said good-bye to his family, and drove away.

When he had

travelled half-way, he met a merchant whom he knew, and they put up at

the same inn for the night. They had some tea together, and then went to

bed in adjoining rooms.

It was not

Aksionov’s habit to sleep late, and, wishing to travel while it was

still cool, he aroused his driver before dawn, and told him to put in

the horses.

Then he made his way

across to the landlord of the inn (who lived in a cottage at the back),

paid his bill, and continued his journey.

When he had gone

about twenty-five miles, he stopped for the horses to be fed. Aksionov

rested awhile in the passage of the inn, then he stepped out into the

porch, and, ordering a samovar to be heated, got out his guitar and

began to play.

Suddenly a troika

drove up with tinkling bells and an official alighted, followed by two

soldiers. He came to Aksionov and began to question him, asking him who

he was and whence he came. Aksionov answered him fully, and said, “Won’t

you have some tea with me?” But the official went on cross-questioning

him and asking him. “Where did you spend last night? Were you alone, or

with a fellow-merchant? Did you see the other merchant this morning? Why

did you leave the inn before dawn?”

Aksionov wondered

why he was asked all these questions, but he described all that had

happened, and then added, “Why do you cross-question me as if I were a

thief or a robber? I am travelling on business of my own, and there is

no need to question me.”

Then the official,

calling the soldiers, said, “I am the police-officer of this district,

and I question you because the merchant with whom you spent last night

has been found with his throat cut. We must search your things.”

They entered the

house. The soldiers and the police-officer unstrapped Aksionov’s luggage

and searched it. Suddenly the officer drew a knife out of a bag,

crying, “Whose knife is this?”

Aksionov looked, and seeing a blood stained knife taken from his bag, he was frightened.

“How is it there is blood on this knife?”

Aksionov tried to

answer, but could hardly utter a word, and only stammered: “I don’t know

- not mine.” Then the police officer said: “This morning the merchant

was found in bed with his throat cut. You are the only person who could

have done it. The house was locked from inside, and no one else was

there. Here is this blood-stained knife in your bag and your face and

manner betray you! Tell me how you killed him, and how much money you

stole?”

Aksionov swore he

had not done it; that he had not seen the merchant after they had had

tea together; that he had no money except eight thousand rubles of his

own, and that the knife was not his. But his voice was broken, his face

pale, and he trembled with fear as though he went guilty.

The police-officer

ordered the soldiers to bind Aksionov and to put him in the cart. As

they tied his feet together and flung him into the cart, Aksionov

crossed himself and wept. His money and goods were taken from him, and

he was sent to the nearest town and imprisoned there. Enquiries as to

his character were made in Vladimir. The merchants and other inhabitants

of that town said that in former days he used to drink and waste his

time, but that he was a good man. Then the trial came on: he was charged

with murdering a merchant from Ryazan, and robbing him of twenty

thousand rubles.

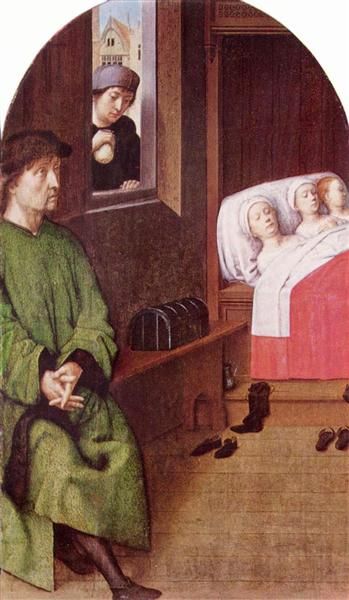

His wife was in

despair, and did not know what to believe. Her children were all quite

small; one was a baby at her breast. Taking them all with her, she went

to the town where her husband was in jail. At first she was not allowed

to see him; but after much begging, she obtained permission from the

officials, and was taken to him. When she saw her husband in

prison-dress and in chains, shut up with thieves and criminals, she fell

down, and did not come to her senses for a long time. Then she drew her

children to her, and sat down near him. She told him of things at home,

and asked about what had happened to him. He told her all, and she

asked, “What can we do now?”

“We must petition the Czar not to let an innocent man perish.”

His wife told him that she had sent a petition to the Czar, but it had not been accepted.

Aksionov did not reply, but only looked downcast.

Then his wife said,

“It was not for nothing I dreamt your hair had turned grey. You

remember? You should not have started that day.” And passing her fingers

through his hair, she said: “Vanya dearest, tell your wife the truth;

was it not you who did it?”

“So you, too,

suspect me!” said Aksionov, and, hiding his face in his hands, he began

to weep. Then a soldier came to say that the wife and children must go

away; and Aksionov said good-bye to his family for the last time.

When they were gone,

Aksionov recalled what had been said, and when he remembered that his

wife also had suspected him, he said to himself, “It seems that only God

can know the truth; it is to Him alone we must appeal, and from Him

alone expect mercy.”

And Aksionov wrote no more petitions; gave up all hope, and only prayed to God.

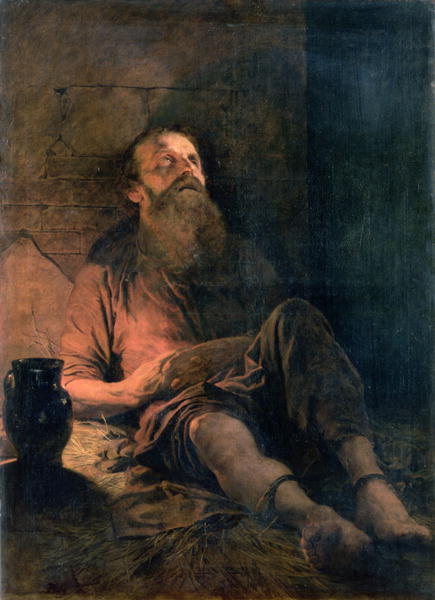

Aksionov was

condemned to be flogged and sent to the mines. So he was flogged with a

knot, and when the wounds made by the knot were healed, he was driven to

Siberia with other convicts.

For twenty-six years

Aksionov lived as a convict in Siberia. His hair turned white as snow,

and his beard grew long, thin, and grey. All his mirth went; he stooped;

he walked slowly, spoke little, and never laughed, but he often prayed.

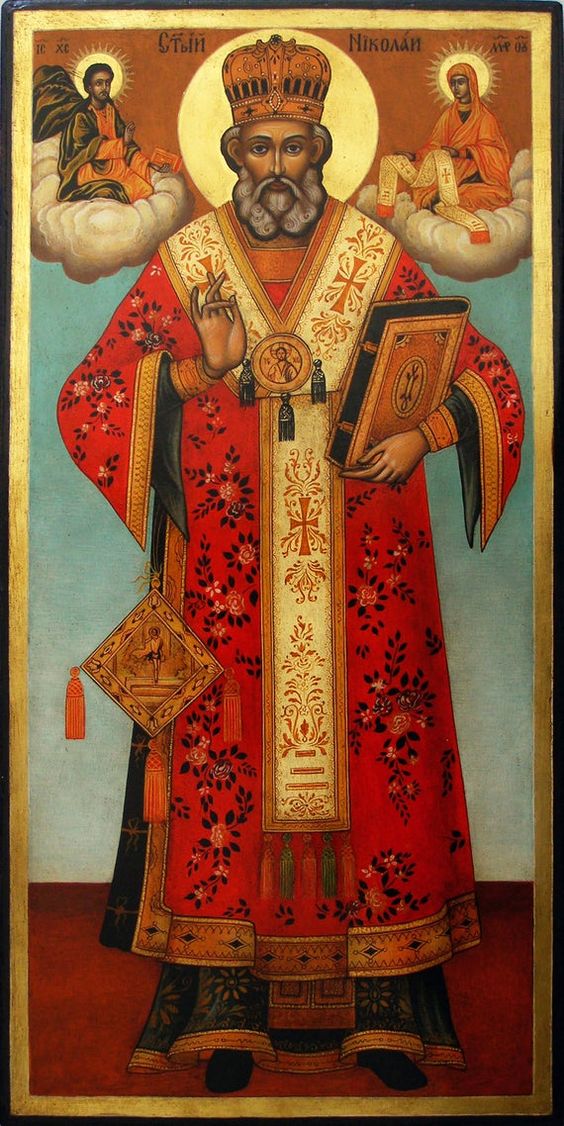

In prison Aksionov

learnt to make boots, and earned a little money, with which he bought

The Lives of the Saints. He read this book when there was light enough

in the prison; and on Sundays in the prison-church he read the lessons

and sang in the choir; for his voice was still good.

The prison

authorities liked Aksionov for his meekness, and his fellow-prisoners

respected him: they called him “Grandfather,” and “The Saint.” When they

wanted to petition the prison authorities about anything, they always

made Aksionov their spokesman, and when there were quarrels among the

prisoners they came to him to put things right, and to judge the matter.

No news reached Aksionov from his home, and he did not even know if his wife and children were still alive.

One day a fresh gang

of convicts came to the prison. In the evening the old prisoners

collected round the new ones and asked them what towns or villages they

came from, and what they were sentenced for. Among the rest Aksionov sat

down near the newcomers, and listened with downcast air to what was

said.

One of the new

convicts, a tall, strong man of sixty, with a closely-cropped grey

beard, was telling the others what he had been arrested for.

“Well, friends,” he

said, “I only took a horse that was tied to a sledge, and I was arrested

and accused of stealing. I said I had only taken it to get home

quicker, and had then let it go; besides, the driver was a personal

friend of mine. So I said, ‘It’s all right.’ ‘No,’ said they, ‘you stole

it.’ But how or where I stole it they could not say. I once really did

something wrong, and ought by rights to have come here long ago, but

that time I was not found out. Now I have been sent here for nothing at

all... Eh, but it’s lies I’m telling you; I’ve been to Siberia before,

but I did not stay long.”

“Where are you from?” asked some one.

“From Vladimir. My family are of that town. My name is Makar, and they also call me Semyonich.”

Aksionov raised his

head and said: “Tell me, Semyonich, do you know anything of the

merchants Aksionov of Vladimir? Are they still alive?”

“Know them? Of

course I do. The Aksionovs are rich, though their father is in Siberia: a

sinner like ourselves, it seems! As for you, Gran’dad, how did you come

here?”

Aksionov did not

like to speak of his misfortune. He only sighed, and said, “For my sins I

have been in prison these twenty-six years.”

“What sins ?” asked Makar Semyonich.

But Aksionov only

said, “Well, well...I must have deserved it !” He would have said no

more, but his companions told the newcomers how Aksionov came to be in

Siberia; how some one had killed a merchant, and had put the knife among

Aksionov’s things, and Aksionov had been unjustly condemned.

When Makar Semyonich

heard this, he looked at Aksionov, slapped his own knee, and exclaimed,

“Well, this is wonderful! Really wonderful! But how old you’ve grown,

Gran’dad !”

The others asked him

why he was so surprised, and where he had seen Aksionov before; but

Makar Semyonich did not reply. He only said: “It’s wonderful that we

should meet here, lads!”

These words made

Aksionov wonder whether this man knew who had killed the merchant; so he

said, “Perhaps, Semyonich, you have heard of that affair, or maybe

you’ve seen me before?”

“How could I help hearing? The world’s full of rumours. But it’s a long time ago, and I’ve forgotten what I heard.”

“Perhaps you heard who killed the merchant?” asked Aksionov.

Makar Semyonich

laughed, and replied: “It must have been him in whose bag the knife was

found! If some one else hid the knife there, ‘He’s not a thief till he’s

caught,’ as the saying is. How could any one put a knife into your bag

while it was under your head? It would surely have woke you up.”

When Aksionov heard

these words, he felt sure this was the man who had killed the merchant.

He rose and went away. All that night Aksionov lay awake. He felt

terribly unhappy, and all sorts of images rose in his mind. There was

the image of his wife as she was when he parted from her to go to the

fair. He saw her as if she were present; her face and her eyes rose

before him; he heard her speak and laugh. Then he saw his children,

quite little, as they were at that time: one with a little cloak on,

another at his mother’s breast. And then he remembered himself as he

used to be-young and merry. He remembered how he sat playing the guitar

in the porch of the inn where he was arrested, and how free from care he

had been. He saw, in his mind, the place where he was flogged, the

executioner, and the people standing around; the chains, the convicts,

all the twenty-six years of his prison life, and his premature old age.

The thought of it all made him so wretched that he was ready to kill

himself.

“And it’s all that

villain’s doing!” thought Aksionov. And his anger was so great against

Makar Semyonich that he longed for vengeance, even if he himself should

perish for it. He kept repeating prayers all night, but could get no

peace. During the day he did not go near Makar Semyonich, nor even look

at him.

A fortnight passed in this way. Aksionov could not sleep at night, and was so miserable that he did not know what to do.

One night as he was

walking about the prison he noticed some earth that came rolling out

from under one of the shelves on which the prisoners slept. He stopped

to see what it was. Suddenly Makar Semyonich crept out from under the

shelf, and looked up at Aksionov with frightened face. Aksionov tried to

pass without looking at him, but Makar seized his hand and told him

that he had dug a hole under the wall, getting rid of the earth by

putting it into his high-boots, and emptying it out every day on the

road when the prisoners were driven to their work.

“Just you keep

quiet, old man, and you shall get out too. If you blab, they’ll flog the

life out of me, but I will kill you first.”

Aksionov trembled

with anger as he looked at his enemy. He drew his hand away, saying, “I

have no wish to escape, and you have no need to kill me; you killed me

long ago! As to telling of you I may do so or not, as God shall direct.”

Next day, when the

convicts were led out to work, the convoy soldiers noticed that one or

other of the prisoners emptied some earth out of his boots. The prison

was searched and the tunnel found. The Governor came and questioned all

the prisoners to find out who had dug the hole. They all denied any

knowledge of it. Those who knew would not betray Makar Semyonich,

knowing he would be flogged almost to death. At last the Governor turned

to Aksionov whom he knew to be a just man, and said:

“You are a truthful old man; tell me, before God, who dug the hole?”

Makar Semyonich

stood as if he were quite unconcerned, looking at the Governor and not

so much as glancing at Aksionov. Aksionov’s lips and hands trembled, and

for a long time he could not utter a word. He thought, “Why should I

screen him who ruined my life? Let him pay for what I have suffered. But

if I tell, they will probably flog the life out of him, and maybe I

suspect him wrongly. And, after all, what good would it be to me?”

“Well, old man,” repeated the Governor, “tell me the truth: who has been digging under the wall?”

Aksionov glanced at

Makar Semyonich, and said, “I cannot say, your honour. It is not God’s

will that I should tell! Do what you like with me; I am in your hands.”

However much the Governor tried, Aksionov would say no more, and so the matter had to be left.

That night, when

Aksionov was lying on his bed and just beginning to doze, some one came

quietly and sat down on his bed. He peered through the darkness and

recognised Makar.

“What more do you want of me?” asked Aksionov. “Why have you come here?”

Makar Semyonich was silent. So Aksionov sat up and said, “What do you want? Go away, or I will call the guard!”

Makar Semyonich bent close over Aksionov, and whispered, “Ivan Dmitrich, forgive me!”

“What for?” asked Aksionov.

“It was I who killed

the merchant and hid the knife among your things. I meant to kill you

too, but I heard a noise outside, so I hid the knife in your bag and

escaped out of the window.”

Aksionov was silent,

and did not know what to say. Makar Semyonich slid off the bed-shelf

and knelt upon the ground. “Ivan Dmitrich,” said he, “forgive me! For

the love of God, forgive me! I will confess that it was I who killed the

merchant, and you will be released and can go to your home.”

“It is easy for you

to talk,” said Aksionov, “but I have suffered for you these twenty-six

years. Where could I go to now?... My wife is dead, and my children have

forgotten me. I have nowhere to go...”

Makar Semyonich did

not rise, but beat his head on the floor. “Ivan Dmitrich, forgive me!”

he cried. “When they flogged me with the knot it was not so hard to bear

as it is to see you now ... yet you had pity on me, and did not tell.

For Christ’s sake forgive me, wretch that I am !” And he began to sob.

When Aksionov heard

him sobbing he, too, began to weep. “God will forgive you!” said he.

“Maybe I am a hundred times worse than you.” And at these words his

heart grew light, and the longing for home left him. He no longer had

any desire to leave the prison, but only hoped for his last hour to

come.

In spite of what

Aksionov had said, Makar Semyonich confessed his guilt. But when the

order for his release came, Aksionov was already dead.