It

was a village fair, and Punch with his usual retinue - Judy, the

Beadle, and the Constable - had established himself on one side of the

green; while on the other were to be seen, Martin, the learned ass, and

Peerless Jacquot, the wonderful parrot. Matthieu la Bouteille (such was

the nickname bestowed upon the owner of the ass, a name justified by the

redness of his nose) held Martin by the bridle, while Peerless Jacquot

rested on his shoulder, attached by a chain to his belt. His wife,

surnamed La Mauricaude, had undertaken to assemble the company, and to

display Martin's talents. Thomas, the son of La Mauricaude, a child of

eleven years of age, covered with a few rags, which had once been a pair

of trowsers and a shirt, collected, in the remnant of a hat, the

voluntary contributions of the spectators; while in the background, sad

and silent, stood Gervais, a lad of between fourteen and fifteen years

of age, Matthew's son by a former marriage.

"Come,

ladies and gentlemen," exclaimed La Mauricaude, in her hoarse voice,

"come and see Martin; he will tell you, ladies and gentlemen, what you

know and what you don't know. Come, ladies and gentlemen, and hear

Peerless Jacquot; he will reply to what you say to him, and to what you

do not say to him." And this joke, constantly repeated by La Mauricaude

in precisely the same tone, always attracted an audience of pretty

nearly the same character.

"Now

then, Martin," continued La Mauricaude, as soon as the circle was

formed, "tell this honourable company what o'clock it is." Martin,

whether he did not understand, or did not choose to reply, still

remained motionless. La Mauricaude renewed the question: Martin shook

his ears. "Do you say, Martin, that you cannot see the clock at this

distance?" continued La Mauricaude. "Has any one a watch?" Immediately

an enormous watch was produced from the pocket of a farmer, and placed

under the eyes of Martin, who appeared to consider it attentively. The

whole assembly, like Martin himself, stretched forward with increased

attention. It was just noon by the watch; after a few moments'

reflection, Martin raised his head and uttered three vigorous hihons, to

which the crowd responded by a burst of laughter, which did not in the

least appear to disturb Martin. "Oh, oh! Martin," cried La Mauricaude,

"I see you are thinking of three o'clock, the time for having your oats;

but you must wait, so what say you to a game of cards, in order to pass

the time?" And a pack of cards, almost effaced by dirt, was immediately

extracted from a linen bag which hung at La Mauricaude's right side,

and spread out in the midst of the circle, which drew in closer, in

order to enjoy a nearer view of the spectacle about to be afforded by

the talents of Martin. "Now then, Martin; now then, my boy," continued

his instructress, "draw: draw first of all the knave of hearts, and

present it to this honourable company as a sign of your attachment and

respect;" and already the two or three wits of the crowd had nodded

their heads with an air of approbation at this ingenious compliment,

when Martin, after repeated orders, put forth his right foot, and placed

it upon the seven of spades.

At

this moment the voice of a parrot was heard in the midst of the crowd,

distinctly pronouncing the words, "That won't do, my good fellow." It

was Peerless Jacquot, who, wearied at not having been called upon to

join in the conversation, repeated one of his favourite phrases. The

appropriateness of his speech restored the good humour of the company,

who were beginning to be disgusted with Martin's stupidity; and their

attention would probably have been bestowed upon Jacquot, had not

Punch's trumpet been at that moment heard, announcing that the actors

were ready and the performances about to commence. At this signal

Martin's audience began to disperse; the ranks thinned, and the remnant

of the hat, which was seen advancing in the hands of Thomas, effectually

drove away those who still lingered from curiosity or indifference. All

took the same direction; and Matthew, Thomas, La Mauricaude, Martin,

and Jacquot followed, with more or less of ill-humour, the crowd which

had deserted them. Gervais alone, separating from them, went into a

neighbouring street to offer his services, during the fair time, to a

farrier engaged in shoeing the horses of the visitors.

A

far different spectacle from any with which Martin could amuse them,

awaited the curious on the other side of the green. An enormous mastiff

had just been unharnessed from a little cart, upon which he had brought

the theatre and company of the Marionettes; and now, lying down in front

of the tent and at the feet of his master, he seemed to take under his

protection those things which had thus far travelled under his

conveyance. Medor's appearance was that of a useful and well-treated

servant; his looks towards his master those of a confiding friend.

Va-bon-train (this was the name of the owner of the Marionettes) might

easily be recognized for an old soldier. The regularity of his movements

added greatly to the effect of their vivacity; everything happened in

its proper turn, and at its proper time. His utterance was precise

without being abrupt, and the tone of military firmness which he

associated with the tricks of his trade, gave to them a certain degree

of dignity. Words taken from the languages of the different countries

through which he had travelled were mingled, with wonderful gravity and

readiness, in the dialogue of the personages whom he put in action; and

scenes in which he had been personally concerned, either as actor or

witness, fired his imagination, and furnished incidents which enabled

him to vary his representations to an unlimited extent. He was assisted

by his son Michael, a fine lad about the age of Gervais, whom he very

much resembled, although the countenance of the one was as serious as

that of the other was cheerful and animated.

There

was nothing strange in this resemblance, for Matthew and Va-bon-train

were brothers, and Michael and Gervais therefore first cousins.

Va-bon-train, whose baptismal name was Vincent, owed his nickname less

to the regularity of his movements than to the vivacity of his

disposition and the promptitude of his determinations. Having at the age

of twenty-five lost his wife, to whom he was much attached, and who had

died in giving birth to Michael, he could not endure even a temporary

grief, and therefore determined, in order to divert his mind, to enter

the army, which he did in the quality of substitute, leaving the price

of his engagement for the support of his son, whom he confided to the

care of Matthew's wife, who had just given birth to Gervais. She nursed

both the children, and brought them up with an equal tenderness and in

good habits, for she was a worthy woman. They went to the same school,

where they learned to read and write, and were instructed in their

religion; they began working together in Matthew's shop, at his trade of

a blacksmith; and, in fine, they were united by a friendship which was

no less ardent on the part of the lively Michael than on that of the

graver Gervais. At the age of thirteen, Gervais had the misfortune of

losing his mother, and almost at the same time the additional one of

being separated from Michael. Vincent Va-bon-train, who had obtained his

discharge, had come for his son, whose assistance he required in

carrying out his enterprise of the Marionettes, in which he had just

engaged. Soon afterwards Matthew's affairs began to fall into confusion.

While his wife lived she had kept a check on his love of drink, but no

sooner was she dead than he gave himself up to it without restraint. At

the tavern he became acquainted with La Mauricaude, a low,

bad-principled woman, who had followed all sorts of trades. He was

foolish enough to marry her, and they soon squandered the little that

remained to him, already much diminished by his disorderly conduct. Then

she persuaded him to give up the shop, and travel through the country

with his ass and his parrot, assuring him that he would thereby gain a

great deal of money. This wandering kind of life accorded better than

regular labour with Matthew's newly-acquired habits; and he was the more

ready to trust the assurances of his wife, as Va-bon-train had just

reappeared in the country in a prosperous condition, the result of the

success of his Marionettes. Matthew then formed the idea of entering

into partnership with his brother; but the latter was not at all anxious

for the connexion, as Matthew's conduct was not calculated to inspire

him with any confidence. His second marriage had displeased him, and he

disliked La Mauricaude, though he had seen her but casually; but a

soldier is not apt to be deterred by trifles, nor to allow his

antipathies to interfere with his actions; and besides, Matthew had

rendered him a service in bringing up his son Michael. For this he was

grateful, and glad, therefore, to have an opportunity of manifesting his

gratitude. The caravan consequently set out, Michael delighted at being

once more with his beloved Gervais, and Gervais sad at leaving the

respectable and regular course of life which suited him, viz. his trade

of blacksmith, in which, notwithstanding his father's negligence in

instructing him, he had already attained some proficiency. He was in

some degree consoled, however, by the prospect of travelling, and

travelling with Michael; and he was glad to leave a place where the

misconduct of his father had ended in destroying the good reputation

which until then his family had always enjoyed.

Unfortunately,

the faults which had destroyed Matthew's reputation followed him

wherever he went. Before the end of the first week, the two parties had

disagreed. The baseness of La Mauricaude, and the wicked propensities of

her son Thomas, who was always better pleased with stealing a thing

than with receiving it as a gift, were soon discovered to Va-bon-train,

in a manner which led him to determine to break his agreement with them

as readily as he had made it; and when he said to his brother, "We must

separate," just as when he said, "We will go together," the matter was

settled, and all opposition was out of the question. Michael no more

thought of opposing his father's resolution than any one else, he only

threw himself weeping into the arms of Gervais, who pressed his hand

sadly, but with resignation, having at least the comfort of thinking

that his uncle would no longer be a witness of the disgraceful conduct

of his family. La Mauricaude was furious, and declared that she was not

to be shaken off in that easy style; and she determined to follow her

brother-in-law, in spite of himself, in order to profit by the crowd he

always attracted, and to endeavour at the same time to injure him,

either by speaking ill of him in every way she could, or by trying to

interrupt his performances, by the shrieks of the parrot, which she had

taught to repeat insulting phrases, and to imitate the voice of the

Marionettes. For two months she persisted in her resolution,

notwithstanding the remonstrances of Matthew, whose remonstrances,

indeed, were usually of very little avail. At first, Va-bon-train was

annoyed with these things; but he soon reconciled himself to them with

his usual promptitude. One day, however, he said to his brother,

"Listen, Matthew: the roads are free; but let me not hear that you have

allowed any one to think that that toad yonder has the insolence to call

herself my sister." So saying, he showed La Mauricaude the whip with

which he was accustomed to give Medor a slight touch now and then, in

order to keep him attentive, and the handle of which had more than once

warned Michael of some failure in discipline. From that time, Gervais no

longer saluted his uncle, for fear of offending him; and La Mauricaude,

notwithstanding her impudence, did not dare to run the risk of braving

him openly. Besides, she would have found it no easy task to entice away

his audience. Who could enter into competition with "the great, the

wonderful, il vero Scaramuccia, Gentlemen, just come direct from Naples,

to present to you, lustrissimi, the homage of his colleagues, the

Lazzaroni? Baccia vu, your hand, Monsu de Scaramouche." And Scaramouche

bowed his head, and raised his hand to his mouth, with a series of

movements capable of making you forget the threads by which they were

directed. "Look, gentlemen, look at Scaramouche, look at him full in the

face; it is indeed Scaramouche; he has not a sou, not a pezzetta,

Gentlemen, but how happy he is! See him with his mouth extended from ear

to ear; his foot raised, ready to run or jump: but one turn of the

hand, one single turn of the wheel of fortune, and behold the

metamorphosis! How anxious and grieved he looks! He is now the Signor

Scaramuccia, he has become rich, he is counting his money in his hand;

he counts, and now he counts more still, and ever with increased

vexation. Oh! what has happened to him now? His countenance is changed.

Oh! what a piteous face! He weeps; he tears his cap. Povero Scaramuccia!

What! presso 'l denaro! Your money has been stolen! Come, come,

Scaramouche, fa cuore, take courage. No!... Ammazarti? You want to kill

yourself! Very well then, but first of all a little Macaroni. Yes, poor

fellow, he will enjoy his Macaroni. See, gentlemen, how piteously he

stretches out his hand, how he eats with tears in his eyes; but, pian

piano, Scaramuccia, gently, vuoi mangiare tutto? Would you eat the

whole? Alas! yes; tutto mangiare, all, per morire! in order that he may

die! What, die of indigestion! You are joking, Scaramouche; Macaroni

never killed a Lazzarone. Stop, see, he revives again; how he draws up

his leg as a mark of pleasure! How he turns his eyes every time he opens

his mouth to receive una copiosa pinch di Macaroni! O che gusto! che

boccone! How delightful! what a mouthful! Make your minds easy,

gentlemen, Scaramouche is alive again." A variety of scenes succeeded,

displaying Scaramouche under numerous aspects, each more admirable than

the former. The last was that in which the German on duty stopped

Scaramouche, with the exclamation Wer da! Scaramouche replied in

Italian, vainly endeavouring to make himself understood, and avoiding,

by dint of suppleness, the terrible bayonet of the German. Then Punch

came up, arguing to as little purpose in French. At length, the Devil

carried away the German, and Punch and Scaramouche went to enjoy a

bottle together.

The

beauty of the invention drew forth enthusiastic and universal applause;

the politicians of the place exchanged mysterious glances; and when

Scaramouche presented to the assembled crowd the little saucer which had

been placed in his hands, there was no one who did not hasten to offer

his sou, his liard, or his centime, for the pleasure of receiving a bow

or a nod from Scaramouche.

The

crowd slowly dispersed, conversing on the pleasure they had enjoyed.

"His Scaramouche breaks my back," said La Mauricaude, in a tone of

ill-temper.

"I have often told you, wife," replied her husband, "that by persisting in following them"....

"I

have often told you, husband, that you are a fool," was the reply of La

Mauricaude. To Matthew it appeared unanswerable; and Thomas, at a look

from his mother, went off to visit Medor, who received him politely, and

with an air of old acquaintanceship. Va-bon-train perceived him,

cracked his great whip, and Thomas immediately ran away as fast as he

could.

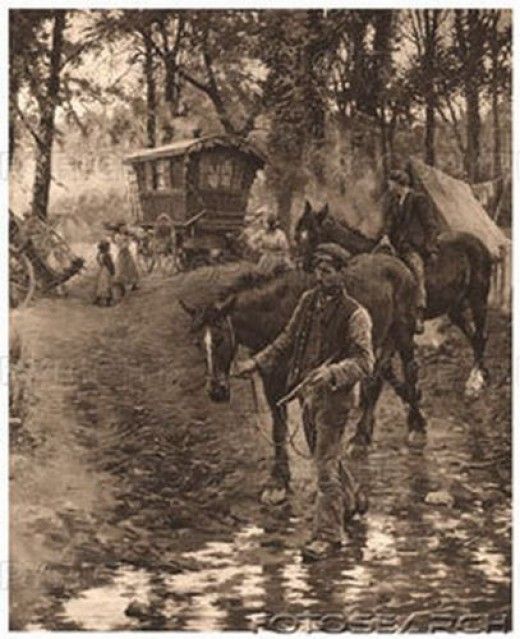

Gervais

was passing along the green, leading back to its owner a horse, which

he had helped to shoe. He did not approach, but Medor perceived him at a

distance, got up, wagged his tail, and gave a slight whine, partly from

the delight of seeing him, and partly from annoyance at not being able

to go with him. Gervais gave him a friendly nod. Michael fondly kissed

the great head of Medor, and a smile seemed to brighten the countenance

of Gervais, at this expression of Michael's affection. It was only in

such ways as this that any interchange of thought was permitted to them.

Though

possessed of many good qualities, Va-bon-train had one defect, - that

of forming precipitate judgments, and of being unwilling to correct them

when formed. He came to a decision at once, in order that a matter

might the sooner be settled; and when he had decided, he did not wish to

be disturbed in his opinion, as it took up too much time to change his

mind. The violence done to his feelings in enduring La Mauricaude for a

whole week had so much increased his prejudice, that it had extended to

the whole family. La Mauricaude was a demon, Matthew a fool, Thomas a

rascal, and Gervais a simpleton. These four judgments once pronounced,

were not to be over-ruled. Va-bon-train was very fond of his son, whose

disposition quite accorded with his own; but he kept him, in military

style, under a strict and prompt obedience, aware that the kind of life

he made him follow, might, without the greatest care, lead a young man

into habits of irregularity and idleness. Fortunately Michael was

possessed of good dispositions, had been well brought up, and preferred

to all other company the society of his father, who amused him with his

numerous anecdotes. Besides, he made it a matter of pride to assist his

father as much as possible, and was never so delighted as when his

exertions had contributed to the success of the day. Va-bon-train's

industry was not confined to his Marionettes; he took advantage of his

constant journeys to carry on a small traffic, purchasing in one canton

such goods as happened to be cheap there, and selling them in some

other, where they were of greater value. He taught Michael how to buy

and sell, and make advantageous speculations; and Michael would have

been perfectly happy in following this kind of busy, useful life, had it

not been for the grief he felt in being unable to share his pleasures

with Gervais. But when, after having slept at the best inn which the

town or village in which they happened to be, afforded, he saw Gervais

in the morning, pale, from having passed a cold or rainy night with no

other shelter than an old barn, his heart was pierced; and,

notwithstanding his father's commands, he found means to get away, and,

with a flask in his hand, hastened to offer a glass of wine to his

friend, who refused it with a shake of the head, but with a friendly

look. Michael sighed; yet this refusal only served to increase his

affection for Gervais; for he well knew that his offer was refused from

honourable feelings, not from pride or rancour. Nor was his mind

relieved, except when Gervais succeeded in finding work; for then he

knew that he would have a good day. When at work, the habitually sad

expression of Gervais' countenance, gave place to an air of animation

quite pleasant to behold; and even Va-bon-train himself had been unable

to resist the temptation of stopping to look at him; and, observing the

dexterity and courage with which he managed the horses, he remarked, "By

my faith, that fellow works well." Then Michael hastened to reply, "Oh!

Gervais is a capital workman;" and he was beginning to add, "and such a

good boy too," when Va-bon-train passed on and spoke of other things.

Michael then contented himself with remaining a little behind, watching

Gervais at work; and when they had exchanged looks, they separated

satisfied.

Up

to that time Gervais had been unsuccessful in his efforts to find a

master who would take him into regular employment. There was no one to

be answerable for him; and those with whom he travelled were not of a

character to give him a recommendation. However, he made the best he

could of his wandering life, by endeavouring to perfect himself in his

trade, losing no opportunity of gaining information, and examining with

care the treatment employed in the various maladies of animals, and all

the other operations of the veterinary art. He also managed to live on

his daily earnings, which he economized with the greatest care, and

thereby escaped the necessity of partaking of the ill-gotten repasts of

La Mauricaude and her son. Sometimes even he shared his own food with

his father, whose wretched life was spent in a state of alternate

intoxication and want, giving himself up to drink the moment he had

money, and the next day going without bread. As it suited La Mauricaude

to have some one who could take care of the ass and the parrot, while

she and her son attended to their own affairs, they were induced to

treat Matthew with some degree of consideration, at least so far as to

allow him a share in their profits, of which, however, they were careful

to conceal from him the source, for Matthew, even in his degraded

condition, preserved an instinct of honesty, which sometimes caused him

to say with a significant air, but only when he was intoxicated, "As for

me, I am an honest man;" for when sober, he had not so much wit. La

Mauricaude had several times endeavoured to get from Gervais the money

he earned, but her demands were always firmly resisted, and Gervais

afterwards took especial care not to leave his money within reach of her

or her son. She had likewise tried to breed dissensions between him and

his father; but Matthew respected his son, and La Mauricaude found that

it was not to her interest to excite too much the attention of Gervais,

for his surveillance would have been very inconvenient to her. She

therefore ended by leaving him in tolerable peace, one reason of which

may have been that she saw little of him, as he usually left the party

as soon as it was day, and did not return until bed-time, when he rarely

slept under a roof, unless it was that of some deserted shed.

The

performances of the morning were over, and Va-bon-train stood chatting

at the door of the inn where he had dined with an old friend, a

blacksmith from Lyons. They were then about twenty-five leagues distant

from that town, on the road to Tournon, whither the blacksmith was going

on some private business. Blanchet, such was this person's name, was

clever at his trade, and well to do in the world. The blacksmith of the

village in which they were then staying was a former apprentice and

workman of his, and he had stopped to visit him as he passed through,

and was now on the point of resuming his journey. The forge was at a

short distance from the inn; and Gervais, who had just left it, as it

was getting dark, came up to the spot where Va-bon-train and Blanchet

were conversing. The street was narrow, and, moreover, partially blocked

up by a horse that was tied in front of the inn. Va-bon-train chancing

to turn his head in the direction by which Gervais was approaching,

perceived him coming, and drew back to allow him to pass. Gervais

blushed and hesitated; he had not been so close to his uncle for two

months. At length he passed on, and, without raising his eyes, bowed to

him as he would have done to a stranger, but with an expression of the

most profound respect. Michael's eyes were suffused with tears, and for a

moment those of Va-bon-train followed his nephew, who, turning round

and encountering his uncle's looks, hastily withdrew his own and

continued his way.

"Do you know that lad ?" demanded Blanchet.

—"Why ?"

"Because yonder at the forge, a short time since, they were talking about you."

—"And what did he say ?" continued Va-bon-train, with an expression of rising displeasure.

—"He?

Nothing:—but one of the men was relating something, I don't know what,

about a woman with whom he had been drinking yesterday, some two leagues

hence, and who told him that you had abandoned your brother in

misfortune. This lad immediately tapped him on the shoulder, saying,

'Comrade, that is no business of yours. It is always best not to

interfere in family quarrels.' The man was silenced; and I, learning

from what passed, that you were here, for I had not then been out upon

the green, I wished to add my word, so I said, that if you did leave

your brother in misfortune, it must be because he deserved it, for I

well knew the kindness of your heart; whereupon, the young fellow gave

me also my answer, though politely enough however, for he said,

'Notwithstanding all that, Master Blanchet, it is much better not to

interfere in family affairs;' and the lad was right as to that; but from

all this I thought he must know you, more especially when, a short time

since, while passing the inn-yard, I saw him enter it, and draw some

water for your dog to drink."

Va-bon-train was visibly moved. Michael, whose heart beat violently, looked at his father.

"He was at work, then, at the blacksmith's?" demanded the latter with some degree of emotion.

"Yes;

and hard at it too, I can tell you. It is vexatious that you do not

know him. He was anxious to be taken as a regular hand there; but when

asked who would be answerable for him, he replied, 'No one.' Had it not

been for this, I would have engaged him myself, for I am sure he will

turn out a capital workman."

"You think so?"

"Oh!

you should see how he sets to work; he would learn more about his

business with me in six months, than with any one else in three years.

But one cannot take him without a recommendation. I heard him say to one

of his companions, that this was the third situation he had lost in

this manner, nor will he ever get one."

"Oh dear!" exclaimed Michael, who could no longer restrain his feelings.

"Well!"

said Va-bon-train. "My friend Blanchet will take him on my

recommendation. Take him, friend; I know him, and will be answerable for

him."

"Nonsense! what are you talking about?"

"Nothing; only that I shall see you at Lyons, whither you are returning:—but when?"

"I shall be there on Monday week."

"And

so shall I; and I will come and dine with you: we will arrange this

matter over our glasses. But, at all events, you will take the lad if I

am answerable for him; do not make me break my word."

"No, no; the thing is settled; good bye till Monday week;" and they parted.

"But Gervais must be told," said Michael, trembling with joy.

"Go,

then, and make haste back; tell him to be at Lyons by Monday week, if

possible; but, above all, he must take care that the old toad knows

nothing about it." This was his usual epithet for La Mauricaude. Michael

departed, and Va-bon-train went to a neighbouring tavern, into which he

had seen Matthew and his company enter. The price of a pair of

stockings worth fifty sous, which had been stolen from a shop at the

fair, and sold a quarter-of-an-hour afterwards for twenty, served to

defray the expenses of the party; and Matthew, owing to the cheapness of

the wine that season, was just on the verge of intoxication, when

Va-bon-train, coming up, said to him, "Matthew, there is but one word

between you and me: when I go one way, you must take care and go the

other; if you don't, your old toad and her young one will every morning

get for their breakfast a sound dressing from this whip."

"As

for me, Vincent, I am an honest man," stammered Matthew. La Mauricaude

was about to vociferate; and the host took part with his customer.

"Friend,"

said Va-bon-train, "when you settle your account with that hussey, I

will not interfere; but look well to the money she gives you:" and he

walked out. As soon as he was gone, La Mauricaude poured forth a torrent

of abuse. Those of her neighbours whose hearts began to be warmed and

their wits clouded by the wine they had taken, agreed unanimously, that

to come and insult in that manner respectable people, who were quietly

taking their glass, without interfering with any one, was a thing not to

be borne: and Matthew again repeated, "As for me, I am an honest man."

The rest, as they looked at La Mauricaude and her son, made some

reflections on Va-bon-train's speech, and the host thought it high time

to demand payment. This completed the ill-humour of La Mauricaude.

As

for Michael, he had hastened to Gervais, and delivered his message. A

sudden flush of surprise and joy suffused the countenance of the latter,

on learning that his uncle would be answerable for him; and when the

voice of Va-bon-train was heard calling his son, the two friends pressed

each other's hands, and parted, each cherishing the thought of the

happiness which was about to dawn for both of them.

All

was quiet at the inn where Va-bon-train had taken up his abode for the

night, when, awaking from his first sleep, he thought he heard Medor in

the yard, groaning, and very uneasy. He went down stairs, and was

surprised to find him tied by a cord to a tree that was near the cart,

and so short that he could scarcely move. As he was accustomed to allow

Medor his liberty at night, feeling quite sure that he would make use of

it only to defend more effectually his master's property, he concluded

that some one had thought to render him a service, by tying up the dog

for fear of his escaping; for in the darkness he had not perceived that

the other end of the cord which attached Medor to the tree, had been

passed round his nose, so as to form a kind of muzzle. Eager to liberate

the poor animal, he cut the cord, which was fastened round his neck by a

slip knot, and which, but for the intervention of his collar, must have

strangled him. The cord once cut, the knot gave way, and, by the aid of

his fore paws, Medor was soon freed from his ignoble fetters. No sooner

had he regained his liberty, than he began to scent with avidity all

round the yard, moaning the whole time; then he dashed against the

stable door as if he would break it in. His master, astonished, opened

it for him, supposing, from what he knew of his instinct, that some

suspicious person might be concealed there; but Medor was contented with

running across the stable, still scenting, to the opposite door, which

led into the street, and which, by the means of this stable, formed one

of the entrances to the inn. His master called him, he came back with

reluctance, and, still moaning, laid down at his feet, as if to solicit a

favour; then he ran to the vehicle, again returned, and rushed with

greater violence against the first door, which his master had in the

mean time closed. Astonished at these manœuvres, Va-bon-train went to

his cart; but everything was in order, the trunk locked, and nothing

apparently to justify the dog's agitation. Then, presuming that Medor,

notwithstanding his good sense, was, like all dogs and all children,

impatient to set out on his journey, and had been seized with this fancy

rather earlier than usual, he gave him a cut with his whip, sent him

back to the cart, and returned to bed.

The

next morning, when he went down, he called Medor, but no Medor

answered. He sought for him everywhere, but without success; he then

recollected what had taken place during the night, and feared that some

one had stolen him.

"Was

he there," demanded one of the travellers, "when you went down in the

night to take something from your cart?" Va-bon-train declared that he

had taken nothing from his cart.

"The

heat was insufferable," continued the man, "and we had the window open.

One of the workmen from the forge, who slept in my room, said: 'See,

there is some one meddling with the box belonging to the exhibitor of

the Marionettes.' 'His dog does not growl,' said I, 'so it must be the

man himself. Never mind, friend; let us sleep.'"

Va-bon-train

hastened to his box, which was still locked; he opened it, and found

everything in disorder: Scaramouche had disappeared, as well as a dozen

of Madras handkerchiefs, the remains of a lot purchased at the fair of

Beaucaire, and the greater part of which had been sold on his journey.

Who could have done this? Va-bon-train remembered having found a key

upon the road, a few days after he had associated himself with Matthew,

and which fitted his trunk. He lost it again the next day, but had not

troubled himself about it. Now he guessed into whose hands it had

fallen, and felt assured that Medor would not have allowed himself to be

approached and led away by any one but an acquaintance.

"That

boy who was at work close by, at the blacksmith's," said the landlord

of the inn, "did he not come in here, and give the dog some drink?"

"He who came with the woman and the ass?" said the hostess. "He seemed to be a respectable lad."

"You

may think so," replied a neighbour; "but when I saw him enter the

stable yonder, after dark, I said to Cateau, What is that little

vagabond going to do there?"

"Gervais!" exclaimed Michael.

"Yes,"

said the landlord, "he was called Gervais at the blacksmith's." The

flush of anger mounted to the face of Va-bon-train. The idea of having

been duped was added to the annoyance of his loss, and he swore that he

would never again be caught overcoming a prejudice. A less hasty

disposition would have examined whether the innkeeper and the neighbour

were not speaking of different persons, and whether suspicion ought not

more naturally to fall upon Thomas and La Mauricaude. But the woman

whose explanations would have thrown light upon the subject had gone

home, and among those who remained there was no one who had seen them,

or, at all events, who would acknowledge to have done so; for where

there is not some falsehood to complicate matters, it is rare that truth

does not break out, so great is its tendency to manifest itself.

Guizot Madame (Elisabeth Charlotte Pauline) 1773-1827

No comments:

Post a Comment