CHAPTER I

THE APOCALYPTIC FRENZY

Two months after the

poisoning of Louis the Do-nothing in 987, Hugh the Capet, Count of

Paris and Anjou, Duke of Isle-de-France, and Abbot of St. Martin of

Tours and St. Germain-des-Pres, had himself proclaimed King by his bands

of warriors, and was promptly consecrated by the Church. By his

ascension to the throne, Hugh usurped the crown of Charles, Duke of

Lorraine, the uncle of Blanche's deceased husband. Hugh's usurpation led

to bloody civil strifes between the Duke of Lorraine and Hugh the

Capet. The latter died in 996 leaving as his successor his son Rothbert,

an imbecile and pious prince. Rothbert's long reign was disturbed by

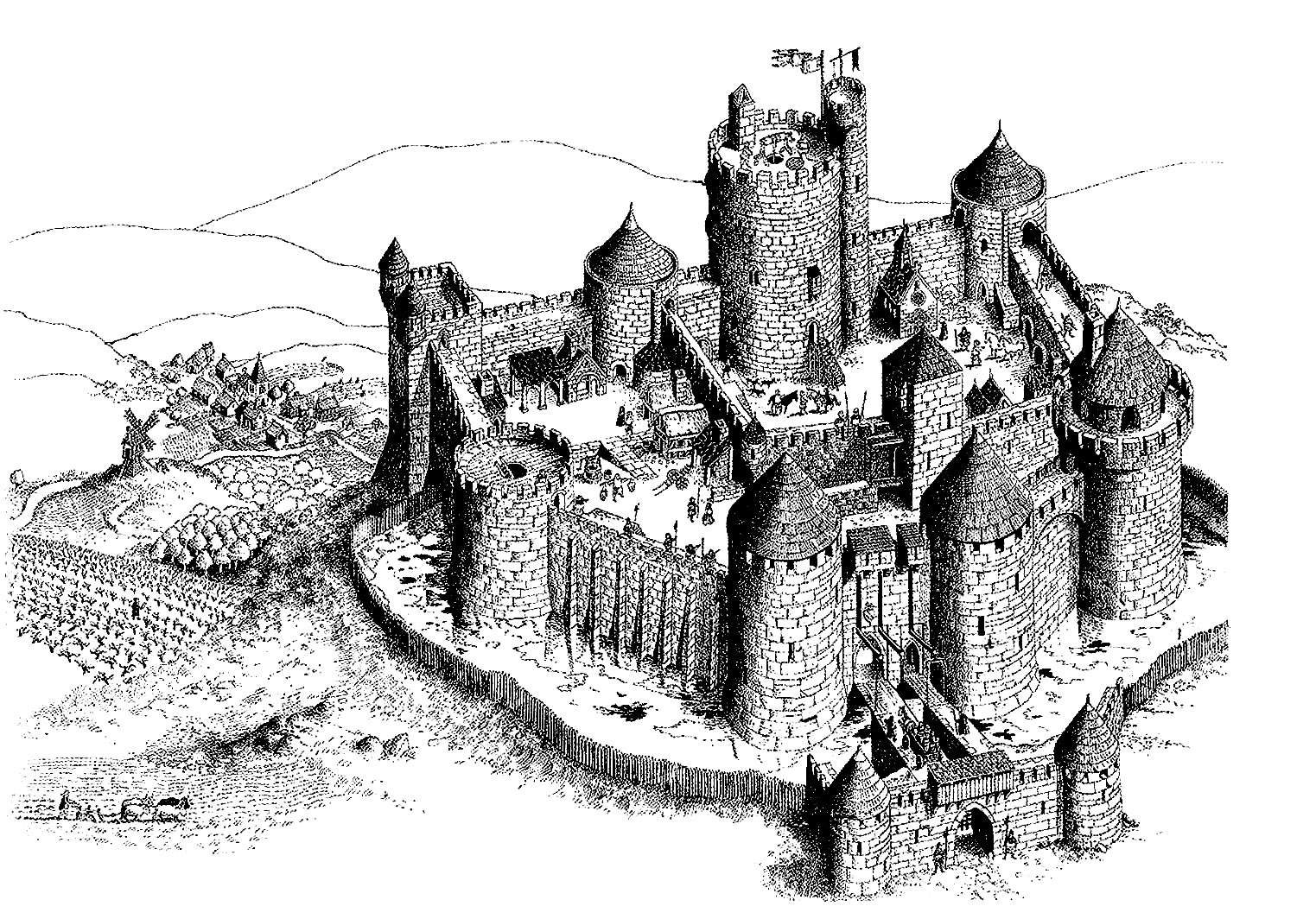

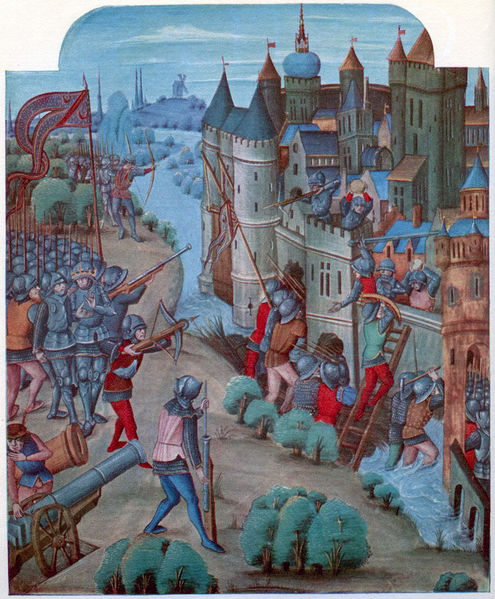

the furious feuds among the seigneurs; counts, dukes, abbots and

bishops, entrenched in their fortified castles, desolated the country

with their brigandage. Rothbert, Hugh's son, died in 1031 and was

succeeded by his son Henry I. His advent to the throne was the signal

for fresh civil strife, caused by his own brother, who was incited

thereto by his mother. Another Rothbert, surnamed the Devil, Duke of

Normandy, a descendant of old Rolf the pirate, took a hand in these

strifes and made himself master of Gisors, Chaumont and Pontoise. It was

under the reign of Hugh the Capet's grandson, Henry I, that the year

1033 arrived, and with it unheard-of, even incredible events, a

spectacle without its equal until then, which was the culmination of the

prevalent myth regarding the end of the world with the year 1000.

The Church had fixed

the last day of the year 1000 as the final term for the world's

existence. Thanks to the deception, the clergy came into possession of

the property of a large number of seigneurs. During the last months of

that year an immense saturnalia was on foot. The wildest passions, the

most insensate, the drollest and the most atrocious acts seemed then

unchained.

"The end of the

world approaches!" exclaimed the clergy. "Did not St. John the Divine

prophesy it in the Apocalypse saying: 'When the thousand years are

expired, Satan will be loosed out of his prison, and shall go out to

deceive the nations which are in the four quarters of the earth; the

book of life will be opened; the sea will give up the dead which were in

it; death and hell will deliver up the dead which were in them; they

will be judged every man according to his works; they will be judged by

Him who is seated upon a brilliant throne, and there will be a new

heaven and a new earth.' - Tremble, ye peoples !" the clergy repeated

everywhere, "the one thousand years, announced by St. John, will run out

with the end of this year! Satan, the anti-Christ is to arrive!

Tremble! The trumpet of the day of judgment is about to sound; the dead

are about to arise from their tombs; in the midst of thunder and

lightning, and surrounded by archangels carrying flaming swords, the

Eternal is about to pass judgment upon us all! Tremble, ye mighty ones

of the earth: in order to conjure away the implacable anger of the

All-Mighty, give your goods to the Church! It is still time! It is still

time! Give your goods and your treasures to the priests of the Lord!

Give all you possess to the Church!"

The seigneurs,

themselves no less brutified than their serfs by ignorance and by the

fear of the devil, and hoping to be able to conjure away the vengeance

of the Eternal, assigned to the clergy by means of authentic documents,

executed in all the forms of terrestrial law, lands, houses, castles,

serfs, their harems, their herds of cattle, their valuable plate, their

rich armors, their pictures, their statues, their sumptuous robes.

Some of the shrewder

ones said: "We have barely a year, a month, a week to live! We are full

of youth, of desires, of ardor! Let us put the short period to profit!

Let us stave-in our wine casks, let us indulge ourselves freely in wine

and women!"

"The end of the

world is approaching!" exclaimed with delirious joy millions of serfs of

the domains of the King, of the lay and of the ecclesiastical

seigneurs. "Our poor bodies, broken with toil, will at last take rest in

the eternal night that is to emancipate us. A blessing on the end of

the world! It is the end of our miseries and our sufferings!"

And those poor

serfs, having nothing to spend and nothing to assign away, sought to

anticipate the expected eternal repose. The larger number dropped their

plows, their hoes and their spades so soon as autumn set in. "What is

the use," said they, "of cultivating a field that, long before harvest

time, will have been swallowed up in chaos?"

As a consequence of

this universal panic, the last days of the year 999 presented a

spectacle never before seen; it was even fabulous! Light-headed

indulgence and groans; peals of laughter and lamentations; maudlin songs

and death dirges. Here the shouts and the frantic dances of supposed

last and supreme orgies; yonder the lamentations of pious canticles. And

finally, floating above this vast mass of terror, rose the formidable

popular curiosity to see the spectacle of the destruction of the world.

It came at last, that day said to have been prophesied by St. John the

Divine! The last hour arrived, the last minute of that fated year of

999! "Tremble, ye sinners!" the warning redoubled; "tremble, ye peoples

of the earth! the terrible moment foretold in the holy books is here!"

One more second, one more instant, midnight sounds and the year 1000

begins.

In the expectation

of that fatal instant, the most hardened hearts, the souls most certain

of salvation, the dullest and also the most rebellious minds experienced

a sensation that never had and never will have a name in any language

Midnight sounded!... The solemn hour.... Midnight!

The year 1000 began !

Oh, wonder and

surprise!... The dead did not leave their tombs, the bowels of the earth

did not open, the waters of the ocean remained within their basins, the

stars of heaven were not hurled out of their orbits and were not

striking against one another in space. Aye, there was not even a tame

flash of lightning! No thunder rolled! No trace of the cloud of fire in

the midst of which the Eternal was to appear. Jehovah remained

invisible. Not one of the frightful prodigies foretold by St. John the

Divine for midnight of the year 1000 was verified. The night was calm

and serene; the moon and stars shone brilliantly in the azure sky, not a

breath of wind agitated the tops of the trees, and the people, in the

silence of their stupor, could hear the slightest ripple of the mountain

streams gliding under the grass. Dawn came ... and day ... and the sun

poured upon creation the torrents of its light! As to miracles, not a

trace of any !

Impossible to

describe the revulsion of feeling at the universal disappointment. It

was an explosion of regret, of remorse, of astonishment, of

recrimination and of rage. The devout people who believed themselves

cheated out of a Paradise that they had paid for to the Church in

advance with hard cash and other property; others, who had squandered

their treasures, contemplated their ruin with trembling. The millions of

serfs who had relied upon slumbering in the restfulness of an eternal

night saw rising anew before their eyes the ghastly dawn of that long

day of misery and sufferings, of which their birth was the morning and

only their death the evening. It now began to be realized that, left

uncultivated in the expectation of the end of the world, the land would

not furnish sustenance to the people, and the horrors of famine were

foreseen. A towering clamor rose against the clergy; the clergy,

however, knew how to bring public opinion back to its side. It did so by

a new and fraudulent set of prophecies.

"Oh, these wretched

people of little faith," thus now ran the amended prophecy and

invocation; "they dare to doubt the word of the All-powerful who spoke

to them through the voice of His prophet! Oh, these wretched blind

people, who close their eyes to divine light! The prophets have

announced the end of time; the Holy Writ foretold that the day of the

last judgment would come a thousand years after the Saviour of the

world!... But although Christ was born a thousand years before the year

1000, he did not reveal himself as God until his death, that is

thirty-two years after his birth. Accordingly it will be in the year

1032 that the end of time will come!"

Such was the general

state of besottedness that many of the faithful blissfully accepted the

new prediction. Several seigneurs, however, rushed at the "men of God"

to take back by force the property they had bequeathed to them. The "men

of God," however, well entrenched behind fortified walls, defended

themselves stoutly against the dispossessed claimants. Hence a series of

bloody wars between the scheming bishops, on the one hand, and the

despoiled seigneurs, on the other, to which disasters were now

superadded the religious massacres instigated by the clergy. The Church

had urged Clovis centuries ago to the extermination of the then Arian

heretics; now the Church preached the extermination of the Orleans

Manichaeans and the Jews. A conception of these abominable excesses may

be gathered from the following passages in the account left by Raoul

Glaber, a monk and eye-witness. He wrote:

"A short time after

the destruction of the Temple of Jerusalem in the year 1010, it was

learned from unquestionable sources that the calamity had to be charged

to the perverseness of Jews of all countries. When the secret leaked out

throughout the world, the Christians decided with a common accord that

they would expel all the Jews, down to the last, from their territories

and towns. The Jews thereby became the objects of universal execration.

Some were chased from the towns, others massacred with iron, or thrown

into the rivers, or put to death in some other manner. This drove many

to voluntary death. And thus, after the just vengeance wreaked upon

them, there were but very few of them left in the Roman Catholic world."

Accordingly, the

wretched Jews of Gaul were persecuted and slaughtered at the order of

the clergy because the Saracens of Judea destroyed the Temple of

Jerusalem! As to the Manichaeans of Orleans, another passage from the

same chronicle expresses itself in these words:

"In 1017, the King

and all his loyal subjects, seeing the folly of these miserable heretics

of Orleans, caused a large pyre to be lighted near the town, in the

hope that fear, produced by the sight, would overcome their

stubbornness; but seeing that they persisted, thirteen of them were cast

into the flames ... and all those that could not be convinced to

abandon their perverse ways met the same fate, whereupon the venerable

cult of the Catholic faith, having triumphed over the foolish

presumption of its enemies, shone with all the greater luster on earth."

What with the wars

that the ecclesiastical seigneurs plunged Gaul into in their efforts to

retain possession of the property of the lay seigneurs whom they had

despoiled by the jugglery of the "End of the World," and what with these

religious persecutions, Gaul continued to be desolated down to the year

1033, the new term that had been fixed for the last day of judgment.

The belief in the approaching dissolution of the world, which the clergy

now again zealously preached, although not so universally entertained

as that of the year 1000, was accompanied with results that were no less

horrible. In 999, the expectation of the end of the world had put a

stop to work; all the fields except those belonging to the

ecclesiastical seigneurs, lay fallow. The formidable famine of the year

1000 was then the immediate result, and that was followed by a

wide-spread mortality. Agriculture pined for laborers; every successive

scarcity engendered an increased mortality; Gaul was being rapidly

depopulated; famine set in almost in permanence during thirty years in

succession, the more disastrous periods being those of the years 1003,

1008, 1010, 1014, 1027, 1029 and 1031; finally the famine of 1033

surpassed all previous ones in its murderous effects. The serfs, the

villeins and the town plebs were almost alone the victims of the

scourge. The little that they produced met the needs of their masters,

the seigneurs, counts, dukes, bishops or abbots; the producers

themselves, however, expired under the tortures of starvation. The

corpses of the wretches who died of inanition strewed the fields, roads

and highways; the decomposing bodies poisoned the air, engendered

illnesses and even pestilential epidemics until then unknown; the

population was decimated. Within thirty-three years, Gaul lost more than

one-half its inhabitants, the new-born babies died vainly pressing

their mother's breasts for nourishment.

CHAPTER II

YVON THE FORESTER'S HUT

Yvon - now no longer

the Calf, but the Forester, since his appointment over the canton of

the Fountain of the Hinds and his family did not escape the scourge.

About five years

before the famine of 1033, his beloved wife Marceline died. He still

inhabited his hut, now shared with him by his son Den-Brao and the

latter's wife Gervaise, together with their three children, of whom the

eldest, Nominoe, was nine, the second, Julyan, seven, and the youngest,

Jeannette, two years of age. Den-Brao, a serf like his father, was since

his youth employed in a neighboring stone quarry. A natural taste for

masonry developed itself in the lad. During his hours of leisure he

loved to carve in certain not over hard stones the outlines of houses

and cottages, the structure of which attracted the attention of the

master mason of Compiegne. Observing Den-Brao's aptitude, the artisan

taught him to hew stone, and soon confided to him the plans of buildings

and the overseership in the construction of several fortified donjons

that King Henry I ordered to be erected on the borders of his domains in

Compiegne. Den-Brao, being of a mild and industrious disposition and

resigned to servitude, had a passionate love for his trade. Often Yvon

would say to him:

"My child, these

redoubtable donjons, whose plans you are sketching and which you build

with so much care, either serve now or will serve some day to oppress

our people. The bones of our oppressed and martyrized brothers will rot

in these subterraneous cells reared above one another with such an

infernal art!"

"Alack! You are

right, father," Den-Brao would at such times answer, "but if not I, some

others will build them ... my refusal to obey my master's orders would

have no other consequence than to bring upon my head a beating, if not

mutilation and even death."

Gervaise, Den-Brao's

wife, an industrious housekeeper, adored her three children, all of

whom, in turn, clung affectionately to Yvon.

The hut occupied by

Yvon and his family lay in one of the most secluded parts of the forest.

Until the year 1033, they had suffered less than other serf families

from the devastations of the recurring famine. Occasionally Yvon brought

down a stag or doe. The meat was smoked, and the provision thus laid by

kept the family from want. With the beginning of the year 1033,

however, one of the epidemics that often afflict the beasts of the

fields attacked the wild animals of the forest of Compiegne. They grew

thin, lost their strength, and their flesh that speedily decomposed,

dropped from their bones. In default of venison, the family was reduced

towards the end of autumn to wild roots and dried berries. They also ate

up the snakes that they caught and that, fattened, crawled into their

holes for the winter. As hunger pressed, Yvon killed and ate his hunting

dog that he had named Deber-Trud in memory of the war-dog of his

ancestor Joel. Subsequently the family was thrown upon the juice of

barks, and then upon the broth of dried leaves. But the nourishment of

dead leaves soon became unbearable, and likewise did the sap-wood, or

second rind of young trees, such as elders and aspen trees, which they

beat to a pulp between stones, have to be given up. At the time of the

two previous famines, some wretched people were said to have supported

themselves with a kind of fattish clay. Not far from Yvon's hut was a

vein of such clay. Towards the end of December, Yvon went out for some

of it. It was a greenish earth of fine paste, soft but heavy, and of

insipid taste. The family thought themselves saved. All its members

devoured the first meal of the clay. But on the morrow their contracted

stomachs refused the nourishment that was as heavy as lead.

CHAPTER III

ON THE BUCK'S TRACK

Thirty-six hours of fast had followed upon the meal of clay in Yvon's hut. Hunger gnawed again at the family's entrails.

During these

thirty-six hours a heavy snow had fallen. Yvon went out. His family was

starving within. He had death on his soul. He went towards the nets that

he had spread in the hope of snaring some bird of passage during the

snow storm. His expectations were deceived. A little distance from the

nets lay the Fountain of the Hinds, now frozen hard. Snow covered its

borders. Yvon perceived the imprint of a buck's feet. The size of the

imprint on the snow announced the animal's bulk. Yvon estimated its

weight by the cracks in the ice on the stream that it had just crossed,

the ice being otherwise thick enough to support Yvon himself. This was

the first time in many months that the forester had run across a buck's

track. Could the animal, perhaps, have escaped the general mortality of

its kind? Did it come from some distant forest? Yvon knew not, but he

followed the fresh track with avidity. Yvon had with him his bow and

arrows. To reach the animal, kill it and smoke its flesh meant the

saving of the lives of his family, now on the verge of starvation. It

meant their life for at least a month. Hope revivified the forester's

energies; he pursued the buck; the regular impress of its steps showed

that the animal was quietly following one of the beaten paths of the

forest; moreover its track lay so clearly upon the snow that he could

not have crossed the stream more than an hour before, else the edges of

the imprint that he left behind him would have been less sharp and would

have been rounded by the temperature of the air. Following its tracks,

Yvon confidently expected to catch sight of the buck within an hour and

bring the animal down. In the ardor of the chase, the forester forgot

his hunger. He had been on the march about an hour when suddenly in the

midst of the profound silence that reigned in the forest, the wind

brought a confused noise to his ears. It sounded like the distant

bellowing of a stag. The circumstance was extraordinary. As a rule the

beasts of the woods do not cry out except at night. Thinking he might

have been mistaken, Yvon put his ear to the ground.... There was no more

room for doubt. The buck was bellowing at about a thousand yards from

where Yvon stood. Fortunately a turn of the path concealed the hunter

from the game. These wild animals frequently turn back to see behind

them and listen. Instead of following the path beyond the turning that

concealed him, Yvon entered the copse expecting to make a short cut,

head off the buck, whose gait was slow, hide behind the bushes that

bordered the path, and shoot the animal when it hove in sight.

The sky was

overcast; the wind was rising; with deep concern Yvon noticed several

snow flakes floating down. Should the snow fall heavily before the buck

was shot, the animal's tracks would be covered, and if opportunity

failed to dart an arrow at it from the forester's ambuscade, he could

not then expect to be able to trace the buck any further. Yvon's fears

proved correct. The wind soon changed into a howling storm surcharged

with thick snow. The forester quitted the thicket and struck for the

path beyond the turning and at about a hundred paces from the clearing.

The buck was nowhere to be seen. The animal had probably caught wind of

its pursuer and jumped for safety into the thicket that bordered the

path. It was impossible to determine the direction that it had taken.

Its tracks vanished under the falling snow, that lay in ever thicker

layers.

A prey to insane

rage, Yvon threw himself upon the ground and rolled in the snow uttering

furious cries. His hunger, recently forgotten in the ardor of the hunt,

tore at his entrails. He bit one of his arms and the pain thus felt

recalled him to his senses. Almost delirious, he rose with the fixed

intent of retracing the buck, killing the animal, spreading himself

beside its carcass, devouring it raw, and not rising again so long as a

shred of meat remained on its bones. At that moment, Yvon would have

defended his prey with his knife against even his own son. Possessed by

the fixed and delirious idea of retracing the buck, Yvon went hither and

thither at hap-hazard, not knowing in what direction he walked. He beat

about a long time, and night began to approach, when a strange incident

came to his aid and dissipated his mental aberration.

CHAPTER IV

GREGORY THE HOLLOW-BELLIED

Driven by the gale,

the snow continued to fall, when suddenly Yvon's nostrils were struck by

the exhalations emitted by frying meat. The odor chimed in with the

devouring appetite that was troubling his senses, and at least bestowed

back upon him the instinct of seeking to satisfy his hunger. He stood

still, whiffed the air hither and thither like a wolf that from afar

scents carrion, and looked about in order to ascertain by the last

glimmerings of the daylight where he was. Yvon was at the crossing of a

path in the forest that led from the little village of Ormesson. The

road ran before a tavern where travelers usually put up for the night.

It was kept by a serf of the abbey of St. Maximim named Gregory, and

surnamed the Hollow-bellied, because, according to him, nothing could

satisfy his insatiable appetite. An otherwise kind-hearted and cheerful

man, the serf often, before these distressful times, and when Yvon

carried his tithe of game to the castle, had accommodatedly offered him a

pot of hydromel. A prey now to the lashings of hunger and exasperated

by the odor of fried meat which escaped from the tavern, Yvon carefully

approached the closed door. In order to allow the smoke to escape,

Gregory had thrown the window half open without fear of being seen. By

the light of a large fire that burned in the hearth, Yvon saw Gregory

seated on a stool placidly surveying the broiling of a large piece of

meat whose odor had so violently assailed the nostrils of the famishing

forester.

To Yvon's great

surprise, the tavern-keeper's appearance had greatly changed. He was no

longer the lean and wiry fellow of before. Now his girth was broad, his

cheeks were full, wore a thick black beard and tinkled with the warm

color of life and health. Within reach of the tavern-keeper lay a

cutlass, a pike and an ax, all red with blood. At his feet an enormous

mastiff picked a bone well covered with meat. The spectacle angered the

forester. He and his family could have lived a whole day upon the

remnants left by the dog; moreover, how did the tavern-keeper manage to

procure so large a loin? Cattle had become so dear that only the

seigneurs and the ecclesiastics could afford to purchase any; beef cost a

hundred gold sous, sheep a hundred silver sous! A sense of hate rose in

Yvon's breast against Gregory whom he had until then looked upon very

much as a friend. The forester could not take his eyes from the meat,

thinking of the joy of his family if he were to return home loaded with

such a booty. For a moment Yvon was tempted to knock at the door of the

serf and demand a share, at least the chunks thrown at the dog. But

judging the tavern-keeper by himself, and noticing, moreover, that the

former was well armed, he reflected that in days like those bread and

meat were more precious than gold and silver; to request Gregory the

Hollow-bellied to yield a part of his supper was folly; he would surely

refuse, and if force was attempted he would kill the intruder. These

thoughts rapidly succeeded one another in Yvon's troubled brain. To add

to his dilemma, his presence was scented by the mastiff who, at first,

growled angrily without, however, dropping his bone, and then began to

bark.

At that moment

Gregory was removing the meat from the spit. "What's the matter, Fillot?

Be brave, old boy! We shall defend our supper. You are furnished with

good strong jaws and fangs, I with weapons. Fear not. No one will

venture to enter. So be still, Fillot! Lie down and keep quiet!" But so

far from lying down and keeping quiet, the mastiff dropped his bone,

stood up, and approaching the window where Yvon stood, barked louder

still. "Oh, oh!" remarked the tavern-keeper depositing the meat in a

large wooden platter on the table. "Fillot drops a bone to bark ...

there must be someone outside." Yvon stepped quickly back, and from the

dark that concealed him he saw Gregory seize his pike, throw the window

wide open and leaning out call with a threatening voice: "Who is there?

If any one is in search of death, he can find it here." The deed almost

running ahead of the thought, Yvon raised his bow, adjusted an arrow

and, invisible to Gregory, thanks to the darkness without, took straight

aim at the tavern-keeper's breast. The arrow whizzed; Gregory emitted a

cry followed by a prolonged groan; his head and bust fell over the

window-sill, and his pike dropped on the snow-covered ground. Yvon

quickly seized the weapon. It was done none too soon. The furious

mastiff leaped out of the window over his dead master's shoulders and

made a bound at the forester. A thrust of the pike nailed the faithful

brute to the ground. Yvon had committed the murder with the ferocity of a

famished wolf. He appeased his hunger. The dizziness that had assailed

his head vanished, his reason returned, and he found himself alone in

the tavern with a still large piece of meat beside him, more than half

of the original chunk.

Feeling as if he

just woke from a dream, Yvon looked around and felt frozen to the

marrow. The light emitted by the hearth enabled him to see distinctly

among the bloody remnants near where the mastiff had been gnawing his

bone, a human hand and the trunk of a human arm. Horrified as he was,

Yvon approached the bleeding members.

There was no doubt.

Before him lay the remains of a human body. The surprising girth that

Gregory the Hollow-bellied had suddenly developed came to his mind. The

mystery was explained. Nourished by human flesh, the monster had been

feeding on the travelers who stopped at his place. The roast that had

just been hungrily swallowed by Yvon proceeded from a recent murder. The

forester's hair stood on end; he dare not look towards the table where

still lay the remains of his cannibal supper. He wondered how his mouth

did not reject the food. But that first and cultivated sense of horror

being over, the forester could not but admit to himself that the meat he

had just gulped down differed little from beef. The thought started a

poignant reflection: "My son, his wife and children are at this very

hour undergoing the tortures of hunger; mine has been satisfied by this

food; however abominable it may be, I shall carry off the rest; the same

as I was at first ignorant of what it was that I ate, my family shall

not know the nature of the dish.... I shall at least have saved them for

a day!" The reasoning matured into resolution.

As Yvon was about to

quit the tavern with his load of human flesh, the gale that had been

howling without and now found entrance through the window, violently

threw open the door of a closet connecting with the room he was in. The

odor of a charnel house immediately assailed the forester's nostrils. He

ran to the hearth, picked up a flaming brand, and looked into the

closet. Its naked walls were bespattered with blood; in a corner lay a

heap of dried twigs and leaves used for kindling a fire and from beneath

them protruded a foot and part of a leg. Yvon scattered the heap of

kindling material with his feet ... they hid a recently mutilated

corpse. The penetrating smell obviously escaped from a lower vault. Yvon

noticed a trap door. Raising it, there rose so putrid an odor that he

staggered back; but driven despite himself to carry his investigation to

the end, he approached the flaming brand to the opening and discovered

below a cavern that was almost filled with bones, heads and other human

members, the bloody remnants of the travelers whom Gregory the

Hollow-bellied had lived upon. In order to put an end to the horrible

spectacle, Yvon hurled his flaming brand into the mortuary cellar; it

was immediately extinguished; for a moment the forester remained in the

dark; he then stepped back into the main room; and overcoming a fresh

assault of human scruple, darted out with the remains of the roast in

his bag, thinking only of his famishing family.

Without, the gale

blew violently; its rage seemed to increase. The moon, then at its

fullest, cast enough light, despite the whirls of snow, to guide Yvon's

steps. He struck the road to the Fountain of the Hinds in haste, moving

with firm though rapid strides. The infernal food he had just partaken

of returned to him his pristine strength. About two leagues from his

hut, he stopped, struck with a sudden thought. The mastiff he had killed

was enormous, fleshy and fat. It could furnish his family with food for

at least three or four days. Why had he forgotten to bring it along?

Yvon turned back to the tavern, long though the road was. As he

approached the house of Gregory he noticed a great brilliancy from afar

and across the falling snow. The light proceeded from the door and

window of the tavern. Only two hours before when he left, the hearth was

extinct and the place dark. Could someone have gone in afterwards and

rekindled the fire ? Yvon crept near the house hoping to carry off the

dog without attracting notice, but voices reached him saying:

"Friends, let us wait till the dog is well roasted."

"I'm hungry! Devilish hungry!"

"So am I ... but I

have more patience than you, who would have eaten the dainty raw....

Pheu! What a smell comes from that charnel room! And yet the door and

window are open!"

"Never mind the smell!... I'm hungry!"

"So, then, Master

Gregory the Hollow-bellied slaughtered the travelers to rob them, I

suppose.... One of them must have been beforehand with him and killed

him.... But the devil take the tavern-keeper! His dog is now roasted.

Let's eat!"

"Let's eat!"

CHAPTER V

THE DELIRIUM OF STARVATION

Too old a man to

think of contesting the spoils for which he had returned to Gregory's

tavern, Yvon hurried back home and reached his hut towards midnight.

On entering, a torch

of resinous wood, fastened near the wall by an iron ring, lighted a

heart-rending spectacle. Stretched out near the hearth lay Den-Brao, his

face covered by his mason's jacket; himself expiring of inanition, he

wished to escape the sight of the agony of his family. His wife,

Gervaise, so thin that the bones of her face could be counted, was on

her knees near a straw pallet where Julyan lay in convulsions. Almost

fainting, Gervaise struggled with her son who was alternately crying

with fury and with pain and in the frenzy of starvation sought to apply

its teeth to his own arms. Nominoe, the elder, lay flat on his face, on

the pallet with his brother. He would have been taken for dead but for

the tremor that from time to time ran over his frame still more

emaciated than his brother's. Finally Jeannette, about three years old,

murmured in her cradle with a dying voice: "Mother ... I am hungry.... I

am hungry!"

At the sound of

Yvon's steps, Gervaise turned her head: "Father!" said she in despair,

"if you bring nothing with you, I shall kill my children to shorten

their agony ... and then myself!"

Yvon threw down his

bow and took his bag from his shoulders. Gervaise judged from its size

and obvious weight that it was full. She wrenched it from Yvon's hands

with savage impatience, thrust her hand in it, pulled out the chunk of

roasted meat and raising it over her head to show it to the whole family

cried out in a quivering voice: "Meat!... Oh, we shall not yet die!

Den-Brao.... Children!... Meat!... Meat!" At these words Den-Brao sat up

precipitately; Nominoe, too feeble to rise, turned on his pallet and

stretched out his eager hands to his mother; little Jeannette eagerly

looked up from her cradle; while Julyan, whom his mother was not now

holding, neither heard nor saw aught but was biting into his arms in the

delirium of starvation, unnoticed by either Yvon or any other member of

the family. All eyes were fixed upon Gervaise, who running to a table

and taking a knife sliced off the meat crying: "Meat!... Meat!"

"Give me!... Give

me!" cried Den-Brao, stretching out his emaciated arms, and he devoured

in an instant the piece that he received.

"You next,

Jeannette!" said Gervaise, throwing a slice to the little girl who

uttered a cry of joy, while her mother herself, yielding to the cravings

of starvation bit off mouthfuls from the slice that she reached out to

her oldest son, Nominoe, who, like the rest, pounced upon the prey, and

fell to eating in silent voracity. "And now, you, Julyan," continued

Gervaise. The lad made no answer. His mother stooped down over him:

"Julyan, do not bite your arm! Here is meat, dear boy!" But his elder

brother, Nominoe, having swallowed up his own slice, brusquely seized

that which his mother was tendering to Julyan. Seeing that the latter

continued motionless, Gervaise insisted: "My child, take your arm from

your teeth!" But hardly had she pronounced these words than, turning

towards Yvon, she cried: "Come here, father.... His arm is icy and rigid

... so rigid that I cannot withdraw it from his jaws."

Yvon rushed to the

pallet where Julyan lay. The little boy had expired in the convulsion of

hunger, although less unfeebled than his brother and sister. "Step

aside," Yvon said to Gervaise; "step aside!" She realized that Julyan

was dead, obeyed Yvon's orders and went on to eat. But her hunger being

appeased, she approached her son's corpse and sobbed aloud:

"My poor little

Julyan!" she lamented. "Oh, my dear child! You died of hunger!... A few

minutes longer and you would have had something to eat like the others

... at least for today!"

"Where did you get this roast, father?" asked Den-Brao.

"I found the tracks

of a buck," answered Yvon dropping his eyes; "I followed the animal but

failed to come up to it. In that way I went as far as the tavern of

Gregory the Hollow-bellied. He was at supper.... I shared his repast,

and he gave me what you have just eaten."

"Such a gift! and in days of famine, father! in such days when only seigneurs and the clergy do not suffer of hunger!"

"I made the

tavern-keeper sympathize with our distress," Yvon answered brusquely,

and, in order to put an end to the subject he added: "I am worn out with

fatigue; I must rest," saying which he walked into the contiguous room

to stretch himself out on his couch, while his son and daughter remained

on their knees near the body of little Julyan. The other two children

fell asleep, still saying they were hungry. After a long and troubled

sleep, Yvon woke up. It was day. Gervaise and her husband still knelt

near Julyan. His brother and sister were saying: "Mother, give us

something to eat; we are hungry!"

"Later, dear little ones," answered the unhappy woman to console them; "later you shall have something to eat."

Den-Brao raised his head and asked: "Where are you going, father?"

"I am going to dig the grave of my little grandson.... I wish to save you the sad task."

"Dig ours also,

father," Den-Brao replied with a dejected mien. "We shall all die

to-night. For a moment allayed, our hunger will rise more violent than

last night ... dig a wide grave for us all."

"Despair not, my children. It has stopped snowing. I may be able to find again the traces of the buck."

Yvon picked up a

spade with which to dig Julyan's grave near where the boy's

great-grandfather, Leduecq, lay buried. Near the place was a heap of

dead branches that had been gathered shortly before by the woodsmen

serfs to turn into coal. After the grave was dug, Yvon left his spade

near it and as the snow had ceased falling he started anew in pursuit of

the buck. It was in vain. Nowhere were the animal's tracks to be seen.

It grew night with the prospect of a long darkness, seeing the moon

would not rise until late. Yvon was reminded by the pangs of hunger,

that began to assail him, that in his hut the sufferings must have

returned. A spectacle, even more distressing than that of the previous

night now awaited him, the convulsive cries of starving children, the

moaning of their mother, the woe-begone looks and dejectment of his son

who lay on the floor awaiting death, and reproaching Yvon for having

prolonged his own and the sufferings of his family with their lives.

Such was the prostration of these wretched beings that, without turning

their heads to Yvon, or even addressing a single word to him, they let

him carry out the corpse of the deceased child.

An hour later Yvon

re-entered his hut. It was pitch dark; the hearth was cold. None had

even the spirit to light a resin torch. Hollow and spasmodic rattlings

were heard from the throats of those within. Suddenly Gervaise jumped up

and groped her way in the dark towards Yvon crying: "I smell roast meat

... just as last night ... we shall not die!... Den-Brao, your father

has brought some more meat!... Come, children, come for your share.... A

light quick!"

"No, no! We want no

light!" Yvon cried in a tremulous voice. "Take!" said he to Gervaise,

who was tugging at the bag on his shoulders. "Take!... Divide this

venison among yourselves, and eat in the dark!"

The wretched family

devoured the meat in the dark; their hunger and feebleness did not allow

them to ask what kind of meat it was. But Yvon fled from the hut almost

crazed with horror. Abomination! His family was again feeding upon

human flesh!

CHAPTER VI

THE FLIGHT TO ANJOU

Long, aimless,

distracted, Yvon wandered about the forest. A severe frost had succeeded

the fall of snow that covered every inch of the ground. The moon shone

brilliantly in the crisp air. The forester felt chilled; in despair he

threw himself down at the foot of a tree, determined there to await

death.

The torpor of death

by freezing was creeping upon the mind of the heart-broken serf when,

suddenly, the crackling of branches that announce the passage of game

fell upon his ears and revived him with the promise of life. The animal

could not be more than fifty paces away. Unfortunately Yvon had left his

bow and arrows in his hut. "It is the buck! Oh, this time I shall kill

him!" he murmured to himself. His revived will-power now dominated the

exhaustion of his forces, and it was strong enough to cause him to lose

no time in vain regrets at not having his hunting arms with him, now

when the prey would be certain. The crackling of the branches drew

nearer. Yvon found himself under a clump of large and old oaks, a little

distance away was the thick copse through which the animal was then

passing. He rose up and planted himself motionless close to and along

the trunk of the tree at the foot of which he had thrown himself down.

Covered by the tree's thickness and the shadow that it threw, with his

neck extended, his eyes and ears on the alert, the serf took his long

forester's knife between his teeth and waited. After several minutes of

mortal suspense, the buck might get the wind of him or come from cover

beyond his reach, Yvon heard the animal approach, then stop an instant

close behind the tree against which he had glued his back. The tree

concealed Yvon from the eyes of the animal, but it also prevented him

from seeing the prey that he breathlessly lay in wait for. Presently,

six feet from Yvon and to the right, he saw plainly sketched upon the

snow, that the light of the moon rendered brilliant, the shape of the

buck and the wide antlers that crowned his head. Yvon stopped breathing

and remained motionless so long as the shadow stood still. A moment

later the shadow began to steal towards him, and with a prodigious bound

Yvon rushed at and seized the animal by the horns. The buck was large

and struggled vigorously; but clambering himself around the horns with

his left arm, Yvon plunged his knife with his right hand into the

animal's throat. The buck rolled over him and expired, while Yvon, with

his mouth fastened to the wound, pumped up and swallowed the blood that

flowed in a thick stream.

The warm and healthy blood strengthened and revivified the serf.... He had not eaten since the previous night.

Yvon rested a few

moments; he then bound the hind legs of the buck with a flexible twig

and dragging his booty, not without considerable effort by reason of its

weight, he arrived with it at his hut near the Fountain of the Hinds.

His family was now for a long time protected from hunger. The buck could

not yield less than three hundred pounds of meat, which carefully

prepared and smoked after the fashion of foresters, could be preserved

for many months.

Two days after these

two fateful nights, Yvon learned from a woodsman serf, that one of his

fellows, a forester of the woods of Compiegne like himself, having

discovered the next morning the body of Gregory the Hollow-bellied

pierced with an arrow that remained in the wound, and having identified

the weapon as Yvon's by the peculiar manner in which it was feathered,

had denounced him as the murderer. The bailiff of the domain of

Compiegne detested Yvon. Although the latter's crime delivered the

neighborhood of a monster who slaughtered the travelers in order to

gorge himself upon them, the bailiff ordered his arrest. Thus notified

in time, Yvon the Forester resolved to flee, leaving his son and family

behind. But Den-Brao as well as his wife insisted upon accompanying him

with their children.

The whole family

decided to take the road and place their fate in the hands of

Providence. The smoked buck's meat would suffice to sustain them through

a long journey. They knew that whichever way they took, serfdom awaited

them. It was a change of serfdom for serfdom; but they found

consolation in the knowledge that the change from the horrors they had

undergone could not but improve their misery. The famine, although

general, was not, according to reports, equally severe everywhere.

The hut near the

Fountain of the Hinds was, accordingly, abandoned. Den-Brao and his wife

carried the little Jeannette by turns on their backs. The other child,

Nominoe, being older, marched besides his grandfather. They reached and

crossed the borders of the royal domain, and Yvon felt safe. A few days

later the travelers learned from some pilgrims that Anjou suffered less

of the famine than did any other region. Thither they directed their

steps, induced thereto by the further consideration that Anjou bordered

on Britanny, the cradle of the family. Yvon wished eventually to return

thither in the hope of finding some of his relatives in Armorica.

The journey to Anjou

was made during the first months of the year 1034 and across a thousand

vicissitudes, almost always accompanied by some pilgrims, or by beggars

and vagabonds. Everywhere on their passage the traces were met of the

horrible famine and not much less horrible ravages caused by the private

feuds of the seigneurs. Little Jeannette perished on the road.

EPILOGUE

The narrative of my

father, Yvon the Forester, breaks off here. He could not finish it. He

was soon after taken sick and died. Before expiring he made to me the

following confession which he desired inserted in the family's annals:

"I have a horrible

confession to make. Near by the grave to which I took the body of

Julyan, lay a large heap of wood that was to be reduced to coal by the

woodsmen. My family was starving in the hut. I saw no way of prolonging

their existence. The thought then occurred to me: 'Last night the

abominable food that I carried to my family from Gregory's human charnel

house kept them from dying in the agonies of starvation. My grandson is

dead. What should I do? Bury the body of little Julyan or have it serve

to prolong the life of those who gave him life?'

"After long

hesitating before such frightful alternatives, the thought of the

agonies that my family were enduring decided me. I lighted the heap of

dried wood. I laid upon it the flesh of my grandson, and by the light

cast from the pyre I buried his bones, except a fragment of his skull,

which I preserved as a sad and solemn relic of those accursed days, and

on which I engraved these fateful words in the Gallic tongue:

Fin-al-bred - The End of the World. I then took the broiled pieces of

meat to my expiring family!... You all ate in the dark.... You knew not

what you ate.... The ghastly meal saved your lives!"

My father then

delivered to me the parchment that contained his narrative, accompanied

with the lettered bone from the skull of my poor little Julyan, and also

the iron arrow-head which accompanied the narrative left by our

ancestor Eidiol, the skipper of Paris. Some day, perhaps, these two

narratives may be joined to the chronicle of our family, no doubt held

by those of our relatives who must still be living in Britanny.

My father Yvon died on the 9th of September, 1034.

This is how our

journey ended: Following my father's wishes and also with the purpose of

drawing near Britanny, we marched towards Anjou, where we arrived on

the territory of the seigneur Guiscard, Count of the region and castle

of Mont-Ferrier. All travelers who passed over his territory had to pay

tribute to his toll-gatherers. Poor people, unable to pay, were,

according to the whim of the seigneur's men, put through some

disagreeable, or humiliating, or ridiculous performance: they were

either whipped, or made to walk on their hands, or to turn somersaults,

or kiss the bolts of the toll-gatherer's gate. As to the women, they

were subjected to revolting obscenities. Many other people as penniless

as ourselves were thus subjected to indignity and brutality. Desirous of

sparing my father and my wife the disgrace, I said to the bailiff of

the seigniory who happened to be there: "The castle I see yonder looks

to me weak in many ways. I am a skillful mason; I have built a large

number of fortified donjons; employ me and I shall work to the

satisfaction of your seigneur. All I ask of you is not to allow my

father, wife and children to be maltreated, and to furnish us with

shelter and bread while the work lasts." The bailiff accepted my offer

gladly, seeing that the mason, who was killed during the last war

against the castle of Mont-Ferrier, had not yet been replaced, and

besides I furnished ample evidence of knowing how to build. The bailiff

assigned us to a hut where we were to receive a serf's pittance. My

father was to cultivate a little garden attached to our hovel, while

Nominoe, then old enough to be of assistance, was to help me at my work

which would last until winter. We contemplated a journey to Britanny

after that. We had lived here five months when, three days ago, I lost

my father.

***

Today the eleventh

day of the month of June, of the year 1035, I, Den-Brao add this

post-script to the above lines that I appended to my father's narrative.

I have to record a sad event. The work on the castle of Mont-Ferrier

not being concluded before the winter of 1034, the bailiff of the

seigneur, shortly after my father's death proposed to me to resume work

in the spring. I accepted. I love my trade. Moreover, my family felt

less wretched here than in Compiegne, and I was not as anxious as my

father to return to Britanny where, after all, there may be no member of

our family left. I accepted the bailiff's offer, and continued to work

upon the buildings, that are now completed. The last piece of work I did

was to finish up a secret issue that leads outside of the castle.

Yesterday the bailiff came to me and said: "One of the allies of the

seigneur of Mont-Ferrier, who is just now on a visit at the castle,

expressed great admiration for the work that you did, and as he is

thinking of improving the fortifications of his own manor, he offered

the count our master to exchange you for a serf who is a skillful

armorer, and whom we need. The matter was settled between them."

"But I am not a serf of the seigneur of Mont-Ferrier," I interposed; "I agreed to work here of my own free will."

The bailiff shrugged

his shoulders and replied: "The law says - every man who is not a

Frank, and who lives a year and a day upon the land of a seigneur,

becomes a serf and the property of the said seigneur, and as such is

subject to taille at will and mercy. You have lived here since the tenth

day of June of the year 1034; we are now at the eleventh day of June of

the year 1035; you have lived a year and a day on the land of the

seigneur of Mont-Ferrier; you are now his serf; you belong to him, and

he has the right to exchange you for a serf of the seigneur of

Plouernel. Drop all thought of resisting our master's will. Should you

kick up your heels, Neroweg IV, seigneur and count of Plouernel, will

order you tied to the tail of his horse, and drag you in that way as far

as his castle."

I would have

resigned myself to my new condition without much grief, but for one

circumstance. For forty years I lived a serf on the domain of Compiegne,

and it mattered little to me whether I exercised my trade of masonry in

one seigniory or another. But I remember that my father told me that he

had it from his grandfather Guyrion how an old family of the name of

Neroweg, established in Gaul since the conquest of Clovis, had ever been

fatal to our own. I felt a sort of terror at the thought of finding

myself the serf of a descendant of the Terrible Eagle - that first of

the Nerowegs that crossed our path.

May heaven ordain it

so that my forebodings prove unfounded! May heaven ordain, my dear son

Nominoe, that you shall not have to register on this parchment aught but

the date of my death and these few words:

"My father Den-Brao ended peaceably his industrious life of a mason serf."

(THE END)

No comments:

Post a Comment