Paris XVIII century

An Episode Adapted from the Memoirs of Maximilian de Bethune, Duke of Sully

What I am going to relate may seem to some merely to be curious and on a party with the diverting story of M. Boisrosé, which I have set down in an earlier part of my memoirs. But among the calumnies of those who have never ceased to attack me since the death of the late king, the statement that I kept from his majesty things which should have reached his ears has always had a prominent place, though a thousand times refuted by my friends, and those who from an intimate acquaintance with events could judge how faithfully I labored to deserve the confidence with which my master honored me. Therefore, I take it in hand to show by an example, trifling in itself, the full knowledge of affairs which the king had, and to prove that in many matters, which were never permitted to become known to the idlers of the court, he took a personal share, worthy as much of Haroun as of Alexander.

It was my custom, before I entered upon those negotiations with the Prince of Condé which terminated in the recovery of the estate of Villebon, where I now principally reside, to spend a part of the autumn and winter at Rosny. On these occasions I was in the habit of leaving Paris with a considerable train of Swiss, pages, valets, and grooms, together with the maids of honor and waiting women of the duchess. We halted to take dinner at Poissy, and generally contrived to reach Rosny toward nightfall, so as to sup by the light of flambeaux in a manner enjoyable enough, though devoid of that state which I have ever maintained, and enjoined upon my children, as at once the privilege and burden of rank.

At the time of which I am speaking I had for my favorite charger the sorrel horse which the Duke of Mercoeur presented to me with a view to my good offices at the time of the king's entry into Paris; and which I honestly transferred to his majesty in accordance with a principle laid down in another place. The king insisted on returning it to me, and for several years I rode it on these annual visits to Rosny. What was more remarkable was that on each of these occasions it cast a shoe about the middle of the afternoon, and always when we were within a short league of the village of Aubergenville. Though I never had with me less than half a score of led horses, I had such an affection for the sorrel that I preferred to wait until it was shod, rather than accommodate myself to a nag of less easy paces; and would allow my household to precede me, staying behind myself with at most a guard or two, my valet, and a page.

The forge at Aubergenville was kept by a smith of some skill, a cheerful fellow, whom I always remembered to reward, considering my own position rather than his services, with a gold livre. His joy at receiving what was to him the income of a year was great, and never failed to reimburse me; in addition to which I took some pleasure in unbending, and learning from this simple peasant and loyal man, what the taxpayers were saying of me and my reforms, a duty I always felt I owed to the king my master.

As a man of breeding it would ill become me to set down the homely truths I thus learned. The conversations of the vulgar are little suited to a nobleman's memoirs; but in this I distinguish between the Duke of Sully and the king's minister, and it is in the latter capacity that I relate what passed on these diverting occasions. "Ho, Simon," I would say, encouraging the poor man as he came bowing and trembling before me, "how goes it, my friend?"

"Badly," he would answer, "very badly until your lordship came this way."

"And how is that, little man?"

"Oh, it is the roads," he always replied, shaking his bald head as he began to set about his business. "The roads since your lordship became surveyor-general are so good that not one horse in a hundred casts a shoe; and then there are so few highwaymen now that not one robber's plates do I replace in a twelvemonth. There is where it is."

At this I was highly delighted.

"Still, since I began to pass this way times have not been so bad with you, Simon," I would answer.

Thereto he had one invariable reply.

"No; thanks to Ste. Geneviève and your lordship, whom we call in this village the poor man's friend, I have a fowl in the pot."

This phrase so pleased me that I repeated it to the king. It tickled his fancy also, and for some years it was a very common remark of that good and great ruler, that he hoped to live to see every peasant with a fowl in his pot.

"But why," I remember I once asked this honest fellow, it was on the last occasion of the sorrel falling lame there "do you thank Ste. Geneviève?"

"She is my patron saint," he answered.

"Then you are a Parisian?"

"Your lordship is always right."

"But does her saintship do you any good?" I asked curiously.

"Certainly, by your lordship's leave. My wife prays to her and she loosens the nails in the sorrel's shoes."

"In fact she pays off an old grudge," I answered, "for there was a time when Paris liked me little; but hark ye, master smith, I am not sure that this is not an act of treason to conspire with Madame Geneviève against the comfort of the king's minister. What think you, you rascal; can you pass the justice elm without a shiver?"

This threw the simple fellow into a great fear, which the sight of the livre of gold speedily converted into joy as stupendous. Leaving him still staring at his fortune I rode away; but when we had gone some little distance, the aspect of his face, when I charged him with treason, or my own unassisted discrimination suggested a clew to the phenomenon.

"La Trape," I said to my valet, the same who was with me at Cahors" what is the name of the innkeeper at Poissy, at whose house we are accustomed to dine?"

"Andrew, may it please your lordship."

"Andrew! I thought so!" I exclaimed, smiting my thigh. "Simon and Andrew his brother! Answer, knave, and, if you have permitted me to be robbed these many times, tremble for your ears. Is he not brother to the smith at Aubergenville who has just shod my horse?"

La Trape professed to be ignorant on this point, but a groom who had stayed behind with me, having sought my permission to speak, said it was so, adding that Master Andrew had risen in the world through large dealings in hay, which he was wont to take daily into Paris and sell, and that he did not now acknowledge or see anything of his brother the smith, though it was believed that he retained a sneaking liking for him.

On receiving this confirmation of my suspicions, my vanity as well as my sense of justice led me to act with the promptitude which I have exhibited in greater emergencies. I rated La Trape for his carelessness of my interests in permitting this deception to be practiced on me; and the main body of my attendants being now in sight, I ordered him to take two Swiss and arrest both brothers without delay. It wanted yet three hours of sunset, and I judged that, by hard riding, they might reach Rosny with their prisoners before bedtime.

I spent some time while still on the road in considering what punishment I should inflict on the culprits; and finally laid aside the purpose I had at first conceived of putting them to death, an infliction they had richly deserved, in favor of a plan which I thought might offer me some amusement. For the execution of this I depended upon Maignan, my equerry, who was a man of lively imagination, being the same who had of his own motion arranged and carried out the triumphal procession, in which I was borne to Rosny after the battle of Ivry. Before I sat down to supper I gave him his directions; and as I had expected, news was brought to me while I was at table that the prisoners had arrived.

Thereupon I informed the duchess and the company generally, for, as was usual, a number of my country neighbors had come to compliment me on my return, that there was some sport of a rare kind on foot; and we adjourned, Maignan, followed by four pages bearing lights, leading the way to that end of the terrace which abuts on the linden avenue. Here, a score of grooms holding torches aloft had been arranged in a circle so that the impromptu theater thus formed, which Maignan had ordered with much taste, was as light as in the day. On a sloping bank at one end seats had been placed for those who had supped at my table, while the rest of the company found such places of vantage as they could; their number, indeed, amounting, with my household, to two hundred persons. In the center of the open space a small forge fire had been kindled, the red glow of which added much to the strangeness of the scene; and on the anvil beside it were ranged a number of horses' and donkeys' shoes, with a full complement of the tools used by smiths. All being ready I gave the word to bring in the prisoners, and escorted by La Trape and six of my guards, they were marched into the arena. In their pale and terrified faces, and the shaking limbs which could scarce support them to their appointed stations, I read both the consciousness of guilt and the apprehension of immediate death; it was plain that they expected nothing less. I was very willing to play with their fears, and for some time looked at them in silence, while all wondered with lively curiosity what would ensue. I then addressed them gravely, telling the innkeeper that I knew well he had loosened each year a shoe of my horse, in order that his brother might profit by the job of replacing it; and went on to reprove the smith for the ingratitude which had led him to return my bounty by the conception of so knavish a trick.

Upon this they confessed their guilt, and flinging themselves upon their knees with many tears and prayers begged for mercy. This, after a decent interval, I permitted myself to grant. "Your lives, which are forfeited, shall be spared," I pronounced. "But punished you must be. I therefore ordain that Simon, the smith, at once fit, nail, and properly secure a pair of iron shoes to Andrew's heels, and that then Andrew, who by that time will have picked up something of the smith's art, do the same to Simon. So will you both learn to avoid such shoeing tricks for the future."

It may well be imagined that a judgment so whimsical, and so justly adapted to the offense, charmed all save the culprits; and in a hundred ways the pleasure of those present was evinced, to such a degree, indeed, that Maignan had some difficulty in restoring silence and gravity to the assemblage. This done, however, Master Andrew was taken in hand and his wooden shoes removed. The tools of his trade were placed before the smith, who cast glances so piteous, first at his brother's feet and then at the shoes on the anvil, as again gave rise to a prodigious amount of merriment, my pages in particular well-nigh forgetting my presence, and rolling about in a manner unpardonable at another time. However, I rebuked them sharply, and was about to order the sentence to be carried into effect, when the remembrance of the many pleasant simplicities which the smith had uttered to me, acting upon a natural disposition to mercy, which the most calumnious of my enemies have never questioned, induced me to give the prisoners a chance of escape. "Listen," I said, "Simon and Andrew. Your sentence has been pronounced, and will certainly be executed unless you can avail yourself of the condition I now offer. You shall have three minutes; if in that time either of you can make a good joke, he shall go free. If not, let a man attend to the bellows, La Trape!"

This added a fresh satisfaction to my neighbors, who were well assured now that I had not promised them a novel entertainment without good grounds; for the grimaces of the two knaves thus bidden to jest if they would save their skins, were so diverting they would have made a nun laugh. They looked at me with their eyes as wide as plates, and for the whole of the time of grace never a word could they utter save howls for mercy. "Simon," I said gravely, when the time was up, "have you a joke? No. Andrew, my friend, have you a joke? No. Then..."

I was going on to order the sentence to be carried out, when the innkeeper flung himself again upon his knees, and cried out loudly, as much to my astonishment as to the regret of the bystanders, who were bent on seeing so strange a shoeing feat "One word, my lord; I can give you no joke, but I can do a service, an eminent service to the king. I can disclose a conspiracy!"

I was somewhat taken aback by this sudden and public announcement. But I had been too long in the king's employment not to have remarked how strangely things are brought to light. On hearing the man's words therefore, which were followed by a stricken silence, I looked sharply at the faces of such of those present as it was possible to suspect, but failed to observe any sign of confusion or dismay, or anything more particular than so abrupt a statement was calculated to produce. Doubting much whether the man was not playing with me, I addressed him sternly, warning him to beware, lest in his anxiety to save his heels by falsely accusing others, he should lose his head. For that if his conspiracy should prove to be an invention of his own, I should certainly consider it my duty to hang him forthwith.

He heard me out, but nevertheless persisted in his story, adding desperately, "It is a plot, my lord, to assassinate you and the king on the same day."

This statement struck me a blow; for I had good reason to know that at that time the king had alienated many by his infatuation for Madame de Verneuil; while I had always to reckon firstly with all who hated him, and secondly with all whom my pursuit of his interests injured, either in reality or appearance. I therefore immediately directed that the prisoners should be led in close custody to the chamber adjoining my private closet, and taking the precaution to call my guards about me, since I knew not what attempt despair might not breed, I withdrew myself, making such apologies to the company as the nature of the case permitted.

I ordered Simon the smith to be first brought to me, and in the presence of Maignan only, I severely examined him as to his knowledge of any conspiracy. He denied, however, that he had ever heard of the matters referred to by his brother, and persisted so firmly in the denial that I was inclined to believe him. In the end he was taken out and Andrew was brought in. The innkeeper's demeanor was such as I have often observed in intriguers brought suddenly to book. He averred the existence of the conspiracy, and that its objects were those which he had stated. He also offered to give up his associates, but conditioned that he should do this in his own way; undertaking to conduct me and one other person, but no more, lest the alarm should be given, to a place in Paris on the following night, where we could hear the plotters state their plans and designs. In this way only, he urged, could proof positive be obtained.

I was much startled by this proposal, and inclined to think it a trap; but further consideration dispelled my fears. The innkeeper had held no parley with anyone save his guards and myself since his arrest, and could neither have warned his accomplices, nor acquainted them with any design the execution of which should depend on his confession to me. I therefore accepted his terms, with a private reservation that I should have help at hand and before daybreak next morning left Rosny, which I had only seen by torchlight, with my prisoner and a select body of Swiss. We entered Paris in the afternoon in three parties, with as little parade as possible, and went straight to the Arsenal, whence, as soon as evening fell, I hurried with only two armed attendants to the Louvre.

A return so sudden and unexpected was as great a surprise to the court as to the king, and I was not slow to mark with an inward smile the discomposure which appeared very clearly on the faces of several, as the crowd in the chamber fell back for me to approach my master. I was careful, however, to remember that this might arise from other causes than guilt. The king received me with his wonted affection; and divining at once that I must have something important to communicate, withdrew with me to the farther end of the chamber, where we were out of earshot of the court. I there related the story to his majesty, keeping back nothing.

He shook his head, saying merely: "The fish to escape the frying pan, grand master, will jump into the fire. And human nature, save in the case of you and me, who can trust one another, is very fishy."

I was touched by this gracious compliment, but not convinced. "You have not seen the man, sire," I said, "and I have had that advantage."

"And believe him?"

"In part," I answered with caution. "So far at least as to be assured that he thinks to save his skin, which he will only do if he be telling the truth. May I beg you, sire," I added hastily, seeing the direction of his glance, "not to look so fixedly at the Duke of Epernon? He grows uneasy."

"Conscience makes you know the rest."

"Nay, sire, with submission," I replied, "I will answer for him; if he be not driven by fear to do something reckless."

"Good! I take your warranty, Duke of Sully," the king said, with the easy grace which came so natural to him. "But now in this matter what would you have me do?"

"Double your guards, sire, for tonight that is all. I will answer for the Bastile and the Arsenal; and holding these we hold Paris."

But thereupon I found that the king had come to a decision, which I felt it to be my duty to combat with all my influence. He had conceived the idea of being the one to accompany me to the rendezvous. "I am tired of the dice," he complained, "and sick of tennis, at which I know everybody's strength. Madame de Verneuil is at Fontainebleau, the queen is unwell. Ah, Sully, I would the old days were back when we had Nerac for our Paris, and knew the saddle better than the armchair!"

"A king must think of his people," I reminded him.

"The fowl in the pot? To be sure. So I will tomorrow," he replied. And in the end he would be obeyed. I took my leave of him as if for the night, and retired, leaving him at play with the Duke of Epernon. But an hour later, toward eight o'clock, his majesty, who had made an excuse to withdraw to his closet, met me outside the eastern gate of the Louvre.

He was masked, and attended only by Coquet, his master of the household. I too wore a mask and was esquired by Maignan, under whose orders were four Swiss, whom I had chosen because they were unable to speak French, guarding the prisoner Andrew. I bade Maignan follow the innkeeper's directions, and we proceeded in two parties through the streets on the left bank of the river, past the Châtelet and Bastile, until we reached an obscure street near the water, so narrow that the decrepit wooden houses shut out well-nigh all view of the sky. Here the prisoner halted and called upon me to fulfill the terms of my agreement. I bade Maignan therefore to keep with the Swiss at a distance of fifty paces, but to come up should I whistle or otherwise give the alarm; and myself with the king and Andrew proceeded onward in the deep shadow of the houses. I kept my hand on my pistol, which I had previously shown to the prisoner, intimating that on the first sign of treachery I should blow out his brains. However, despite precaution, I felt uncomfortable to the last degree. I blamed myself severely for allowing the king to expose himself and the country to this unnecessary danger; while the meanness of the locality, the fetid air, the darkness of the night, which was wet and tempestuous, and the uncertainty of the event lowered my spirits, and made every splash in the kennel and stumble on the reeking, slippery pavements matters over which the king grew merry, seem no light troubles to me.

Arriving at a house, which, if we might judge in the darkness, seemed to be of rather greater pretensions than its fellows, our guide stopped, and whispered to us to mount some steps to a raised wooden gallery, which intervened between the lane and the doorway. On this, besides the door, a couple of unglazed windows looked out. The shutter of one was ajar, and showed us a large, bare room, lighted by a couple of rushlights. Directing us to place ourselves close to this shutter, the innkeeper knocked at the door in a peculiar fashion, and almost immediately entered, going at once into the lighted room. Peering cautiously through the window we were surprised to find that the only person within, save the newcomer, was a young woman, who, crouching over a smoldering fire, was crooning a lullaby while she attended to a large black pot.

"Good evening, mistress!" said the innkeeper, advancing to the fire with a fair show of nonchalance.

"Good evening, Master Andrew," the girl replied, looking up and nodding, but showing no sign of surprise at his appearance. "Martin is away, but he may return at any moment."

"Is he still of the same mind?"

"Quite."

"And what of Sully? Is he to die then?" he asked.

"They have decided he must," the girl answered gloomily. It may be believed that I listened with all my ears, while the king by a nudge in my side seemed to rally me on the destiny so coolly arranged for me. "Martin says it is no good killing the other unless he goes too, they have been so long together. But it vexes me sadly, Master Andrew," she added with a sudden break in her voice. "Sadly it vexes me. I could not sleep last night for thinking of it, and the risk Martin runs. And I shall sleep less when it is done."

"Pooh-pooh!" said that rascally innkeeper. "Think less about it. Things will grow worse and worse if they are let live. The King has done harm enough already. And he grows old besides."

"That is true!" said the girl. "And no doubt the sooner he is put out of the way the better. He is changed sadly. I do not say a word for him. Let him die. It is killing Sully that troubles me, that and the risk Martin runs."

At this I took the liberty of gently touching the king. He answered by an amused grimace; then by a motion of his hand he enjoined silence. We stooped still farther forward so as better to command the room. The girl was rocking herself to and fro in evident distress of mind. "If we killed the King," she continued, "Martin declares we should be no better off, as long as Sully lives. Both or neither, he says. But I do not know. I cannot bear to think of it. It was a sad day when we brought Epernon here, Master Andrew; and one I fear we shall rue as long as we live."

It was now the king's turn to be moved. He grasped my wrist so forcibly that I restrained a cry with difficulty. "Epernon!" he whispered harshly in my ear. "They are Epernon's tools! Where is your guaranty now, Rosny?"

I confess that I trembled. I knew well that the king, particular in small courtesies, never forgot to call his servants by their correct titles, save in two cases; when he indicated by the seeming error, as once in Marshal Biron's affair, his intention to promote or degrade them; or when he was moved to the depths of his nature and fell into an old habit. I did not dare to reply, but listened greedily for more information.

"When is it to be done?" asked the innkeeper, sinking his voice and glancing round, as if he would call especial attention to this.

"That depends upon Master la Rivière," the girl answered. "Tomorrow night, I understand, if Master la Rivière can have the stuff ready."

I met the king's eyes. They shone fiercely in the faint light, which issuing from the window fell on him. Of all things he hated treachery most, and La Rivière was his first body physician, and at this very time, as I well knew, was treating him for a slight derangement which the king had brought upon himself by his imprudence. This doctor had formerly been in the employment of the Bouillon family, who had surrendered his services to the king. Neither I nor his majesty had trusted the Duke of Bouillon for the last year past, so that we were not surprised by this hint that he was privy to the design.

Despite our anxiety not to miss a word, an approaching step warned us at this moment to draw back. More than once before we had done so to escape the notice of a wayfarer passing up and down. But this time I had a difficulty in inducing the king to adopt the precaution. Yet it was well that I succeeded, for the person who came stumbling along toward us did not pass, but, mounting the steps, walked by within touch of us and entered the house.

"The plot thickens," muttered the king. "Who is this?"

At the moment he asked I was racking my brain to remember. I have a good eye and a fair recollection for faces, and this was one I had seen several times. The features were so familiar that I suspected the man of being a courtier in disguise, and I ran over the names of several persons whom I knew to be Bouillon's secret agents. But he was none of these, and obeying the king's gesture, I bent myself again to the task of listening.

The girl looked up on the man's entrance, but did not rise. "You are late, Martin," she said.

"A little," the newcomer answered. "How do you do, Master Andrew? What cheer? What, still vexing, mistress?" he added contemptuously to the girl. "You have too soft a heart for this business!"

She sighed, but made no answer.

"You have made up your mind to it, I hear?" said the innkeeper.

"That is it. Needs must when the devil drives!" replied the man jauntily. He had a downcast, reckless, luckless air, yet in his face I thought I still saw traces of a better spirit.

"The devil in this case was Epernon," quoth Andrew.

"Aye, curse him! I would I had cut his dainty throat before he crossed my threshold," cried the desperado. "But there, it is too late to say that now. What has to be done, has to be done."

"How are you going about it? Poison, the mistress says."

"Yes; but if I had my way," the man growled fiercely, "I would out one of these nights and cut the dogs' throats in the kennel!"

"You could never escape, Martin!" the girl cried, rising in excitement. "It would be hopeless. It would merely be throwing away your own life."

"Well, it is not to be done that way, so there is an end of it," quoth the man wearily. "Give me my supper. The devil take the king and Sully too! He will soon have them."

On this Master Andrew rose, and I took his movement toward the door for a signal for us to retire. He came out at once, shutting the door behind him as he bade the pair within a loud good night. He found us standing in the street waiting for him and forthwith fell on his knees in the mud and looked up at me, the perspiration standing thick on his white face. "My lord," he cried hoarsely, "I have earned my pardon!"

"If you go on," I said encouragingly, "as you have begun, have no fear." Without more ado I whistled up the Swiss and bade Maignan go with them and arrest the man and woman with as little disturbance as possible. While this was being done we waited without, keeping a sharp eye upon the informer, whose terror, I noted with suspicion, seemed to be in no degree diminished. He did not, however, try to escape, and Maignan presently came to tell us that he had executed the arrest without difficulty or resistance.

The importance of arriving at the truth before Epernon and the greater conspirators should take the alarm was so vividly present to the minds of the king and myself, that we did not hesitate to examine the prisoners in their house, rather than hazard the delay and observation which their removal to a more fit place must occasion. Accordingly, taking the precaution to post Coquet in the street outside, and to plant a burly Swiss in the doorway, the king and I entered. I removed my mask as I did so, being aware of the necessity of gaining the prisoners' confidence, but I begged the king to retain his. As I had expected, the man immediately recognized me and fell on his knees, a nearer view confirming the notion I had previously entertained that his features were familiar to me, though I could not remember his name. I thought this a good starting point for my examination, and bidding Maignan withdraw, I assumed an air of mildness and asked the fellow his name.

"Martin, only, please your lordship," he answered; adding, "once I sold you two dogs, sir, for the chase, and to your lady a lapdog called Ninette no larger than her hand."

I remembered the knave, then, as a fashionable dog dealer, who had been much about the court in the reign of Henry the Third and later; and I saw at once how convenient a tool he might be made, since he could be seen in converse with people of all ranks without arousing suspicion. The man's face as he spoke expressed so much fear and surprise that I determined to try what I had often found successful in the case of greater criminals, to squeeze him for a confession while still excited by his arrest, and before he should have had time to consider what his chances of support at the hands of his confederates might be. I charged him therefore solemnly to tell the whole truth as he hoped for the king's mercy. He heard me, gazing at me piteously; but his only answer, to my surprise, was that he had nothing to confess.

"Come, come," I replied sternly, "this will avail you nothing; if you do not speak quickly, rogue, and to the point, we shall find means to compel you. Who counseled you to attempt his majesty's life?"

On this he stared so stupidly at me, and exclaimed with so real an appearance of horror: "How? I attempt the king's life? God forbid!" that I doubted that we had before us a more dangerous rascal than I had thought, and I hastened to bring him to the point.

"What, then," I cried, frowning, "of the stuff Master la Rivière is to give you to take the king's life to-morrow night? Oh, we know something, I assure you; bethink you quickly, and find your tongue if you would have an easy death."

I expected to see his self-control break down at this proof of our knowledge of his design, but he only stared at me with the same look of bewilderment. I was about to bid them bring in the informer that I might see the two front to front, when the female prisoner, who had hitherto stood beside her companion in such distress and terror as might be expected in a woman of that class, suddenly stopped her tears and lamentations. It occurred to me that she might make a better witness. I turned to her, but when I would have questioned her she broke into a wild scream of hysterical laughter.

From that I remember that I learned nothing, though it greatly annoyed me. But there was one present who did, the king. He laid his hand on my shoulder, gripping it with a force that I read as a command to be silent.

"Where," he said to the man, "do you keep the King and Sully and Epernon, my friend?"

"The King and Sully, with the lordship's leave," said the man quickly, with a frightened glance at me "are in the kennels at the back of the house, but it is not safe to go near them. The King is raving mad, and...and the other dog is sickening. Epernon we had to kill a month back. He brought the disease here, and I have had such losses through him as have nearly ruined me, please your lordship."

"Get up, get up, man!" cried the king, and tearing off his mask he stamped up and down the room, so torn by paroxysms of laughter that he choked himself when again and again he attempted to speak.

I too now saw the mistake, but I could not at first see it in the same light. Commanding myself as well as I could, I ordered one of the Swiss to fetch in the innkeeper, but to admit no one else.

The knave fell on his knees as soon as he saw me, his cheeks shaking like a jelly.

"Mercy, mercy!" was all he could say.

"You have dared to play with me?" I whispered.

"You bade me joke," he sobbed, "you bade me."

I was about to say that it would be his last joke in this world for my anger was fully aroused when the king intervened.

"Nay," he said, laying his hand softly on my shoulder. "It has been the most glorious jest. I would not have missed it for a kingdom. I command you, Sully, to forgive him."

Thereupon his majesty strictly charged the three that they should not on peril of their lives mention the circumstances to anyone. Nor to the best of my belief did they do so, being so shrewdly scared when they recognized the king that I verily think they never afterwards so much as spoke of the affair to one another. My master further gave me on his own part his most gracious promise that he would not disclose the matter even to Madame de Verneuil or the queen, and upon these representations he induced me freely to forgive the innkeeper. So ended this conspiracy, on the diverting details of which I may seem to have dwelt longer than I should; but alas! in twenty-one years of power I investigated many, and this one only can I regard with satisfaction. The rest were so many warnings and predictions of the fate which, despite all my care and fidelity, was in store for the great and good master I served.

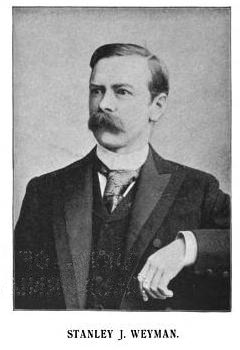

Stanley John Weyman (1855 – 1928) was an English writer of historical romance. His most popular works were written in 1890–1895 and set in late 16th and early 17th-century France. While very successful at the time, they are now largely forgotten.